Henry Kulka 1900-1971 (Architects of Remuera) a forerunner of New Zealand modern architecture

Henry Kulka (1900–71) is often cited as a forerunner of New Zealand modern architecture. Alongside Ernst Plischke, Kulka is the most significant emigree architect ever to work in this country. However, outside of a few surviving houses, most notably the Halberstam House, Karori, Wellington, 1948, his actual work remains little published in this country and the state of his legacy today is fragile.

Kulka was born Jindřich in 1900, in Moravia, eastern Czechia. He later changed his name to the more Germanic-sounding Heinrich. Later again, upon arrival in New Zealand, he would change it to the anglicised Henry.

Henry Kulka studied under, worked alongside and is most strongly associated with Czech architect Adolf Loos (1870–1933). Loos was one of the key polemicists of modern architecture and author of the foundational text, Ornament and Crime, published 1913. Loos was also architect of, amongst many other works, the American Bar, 1908, Vienna, the hugely controversial Goldman and Salatsch Building, Michaelerplatz, Vienna, 1910–12 (now the Raiffeisenbank), and late in life, Villa Müller, Prague (1928), now recognised as one of the key private houses of modern architecture.

From his death in 1933, until the late 1970s, Loos was largely a neglected figure. Today, by contrast, his is work is subject to an insatiable and growing library of books, international conferences and articles, both scholarly and popular. There are numerous, ongoing efforts to restore his surviving works in Brno, Pilsen, Prague and Vienna, and elsewhere in Austria and Czechia. Over the past decade, a number of his surviving buildings have become major architectural tourist attractions.

In 1919, Kulka became a student of Adolf Loos’s Bauschule, Loos’s self-initiated alternative to Vienna’s architecture school system. From 1920 until 1923, Kulka was a student trainee in Loos’s office, working on the Heuberg Siedlung (housing estate), Vienna.

In 1921, Kulka aided Loos in the editing and compilation of Loos’s writings, later translated into English as Spoken into the Void.[1] Kulka worked on the Chicago Tribune Tower international architectural competition, 1922, a colossal Doric column which the jury did not award a prize to, but which has gone on to become one of the most iconic images of modernism. It was focus of extended treatment in Post Modern Architecture, 1977 by English architectural critic Charles Jencks. He viewed Loos’s tower as a forerunner to postmodernism, with its interest in symbolism and classicism and even, as Jencks saw it, irony and wit.

In 1922 Kulka worked under Loos on the Villa Rufer in Hietzing, Vienna. This is often considered Loos’s breakthrough project in terms of organising spaces according to Raumplan principles; that is, a three-dimensional assembly of volumes, with rooms of differing heights depending on their importance and intended atmosphere, locked together within the one simple outer cube.

In 1924, when Loos moved to Paris, Kulka continued as his technical manager in Vienna. Kulka’s wife Hilde (later Hilda) Beran became the practice manager for Loos’s office and later Kulka’s as well. In 1927 Kulka moved to Paris to join Loos. Here he supervised the alterations to Loos’s Kniže menswear store on the Champs-Élysées (demolished) and assisted on the unrealised house for world-famous dancer Josephine Baker.

In 1928 Kulka and Loos returned to Vienna. Kulka assisted Loos’s employee Jacques Groag (architect husband of textile designer Jacqueline Groag) on Loos’s key late work, Villa Moller, Vienna. Kulka wrote the first monograph on Loos, published in 1931 under Loos’s direction, Adolf Loos: Das werk des architecten, published by Anton Schroll Verlag.[2] Loos and Kulka commissioned photographer Martin Gerlach Jnr to revisit and document Loos’s entire oeuvre. Kulka is credited with the first use of the term Raumplan, though it was not one which Loos himself ever used. Later, in 1957, by which time Loos was an almost forgotten figure, Kulka wrote a lengthy and detailed article on Loos in the British publication, Architect’s Year Book.[3]

Kulka’s writing on Loos was almost unique, until joined by Münz and Kunstler’s book of 1964, reproduced in English in 1966, with an introduction by architectural historian Nicholas Pevsner.[3] Kulka was thus not only a promotor of Loos, but also one of his first interpreters as well as his key disciple.

By the 1930’s, Kulka had assumed a senior position in Loos’s office, considered by many critics to be almost Loos’s co-worker, rather than employee. Kulka was co-architect with Loos Albert Matzner shop along Kohlmessergasse, Vienna, 1930 (demolished), on Landhaus Khuner, Payerbach (1930), a holiday house which today operates as a family-run hotel, about one hour south of Vienna by train, and on the Werkbundsiedlung houses, Hietzing, Vienna, 1932–33, which also still exist. Together Loos and Kulka ran the studio until 1932 when Loos could no longer continue in practice due to ill health.

As well as being highly regarded by Loos professionally, Kulka and Loos were close personally. Kulka was best man at Adolf Loos’s wedding in 1929 to Claire Beck, Loos’s third wife. Claire wrote an account of her marriage to Loos after his death, to help raise money for his permanent tombstone, later translated into English as the work The Private Adolf Loos: A Private Portrait.[4] She died at the hands of the Nazis in 1942.

A large number of Loos’s clients and key workers were Jewish. Many died in the Holocaust or had their houses possessed first by the Nazis and later the communists and so were both displaced and dispossessed, if they were fortunate enough to survive at all. It is a miracle so many of Loos’s works still exist today.

After Loos’s death in 1933, Kulka continued to practise, with an office in Vienna and a second one in Hradec Králové, Czechia. Under his own name he completed a number of works including buildings in Vienna (Villa Weissmann, 1934), Jablonec nad Nisou (Villa Kantor, 1932–34), Prague (Kniže menswear store, 1934), Vienna (the stunning Parker Pen shop,1935), Hradec Králové (the Löwenbach apartment building, 1938) and Hronov (Villa Holzner, 1938).

Imagine being at the centre of European cultural life, giving it all up However, as a Jewish architect, following the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany in 1938, Kulka was forced give up the life, contacts, and the reputation he had built up over the preceding decades and escape the coming wave of systematic murder. First, the family (including young children Richard and Maru) fled to England then, with letters of introduction from composer Arnold Schönberg and diplomat Jan Masaryk among other major cultural figures, they travelled to New Zealand in March, 1940.

Here Kulka built a number of fine timber houses during the 1940s and again towards the end of his career, in the 1960s. Many of these works were designed for fellow Jewish emigres who recognised his talents and shared his cultural heritage. From 1940 until 1960, Henry Kulka worked at Fletcher Construction, New Zealand’s major building company, as an architect, rising to the position of their Chief Architect. He not only designed buildings across the country for Fletchers, but he also designed several significant houses and wide-ranging alterations for the Fletcher family. By some accounts, Kulka designed around forty private houses in New Zealand and over a hundred commercial and industrial buildings, including head office buildings, factories and also churches.

At one time, Kulka’s buildings could be found as far north as Whangarei, in the Auckland suburbs of Remuera, Epsom, St Heliers, Glendowie, Howick and Manurewa; in the Waikato, Kawerau, Wellington, Christchurch, as far south as Dunedin and as far north as Apia, Samoa. Henry Kulka died in 1971 and is buried in West Auckland, in the Hebrew area of Waikumete Cemetery. His wife Hilda is also buried at Waikumete, in the newer liberal Jewish area. His descendants live in New Zealand and Israel.

Today, almost all of this industrial heritage has disappeared. Sadly too, very little of his New Zealand private housing survives in anywhere near original condition. Kulka was rarely published in New Zealand in his own lifetime, which is hard to square with someone who so successfully used the media to promote Loos. His archive is of international significance to the study of Loos. It is also, of course, vital for advancing understanding of his own work, as arguably Loos’s most talented colleague. However, it remains private. Since his death, and lacking the publicity he deserved, the greater part of Kulka’s private housing has been demolished or been altered beyond recognition. Regularly his houses have sold without any awareness of who the original architect was, let alone his world-class pedigree. This process of destruction has continued right up until the present day, with several works being lost even in the past year alone.

In Europe, by contrast, the situation is finally improving. Considerable state-funded efforts have gone into the lengthy restoration of one of Kulka’s key works, the fabulous interior of Apartment Semler, Pilsen, 1932–34. It reopened to the public late 2022 after restoration works which began over a decade ago. This work, it is assumed, originated in a concept sketch by Loos. However, its design was developed when Loos was gravely ill, and it was only built after Loos’s death. It is now understood as a joint work and promoted by the city of Pilsen as a Loos / Kulka building. This work looks set to begin the proper re-evaluation of Kulka’s individual talents in Europe. Almost inevitably, it will lead to international Loos scholars making renewed efforts to seek out his work in New Zealand.

Henry Kulka is a key bridge between New Zealand and the vital heart of early European modernism. Imagine being at the centre of European cultural life, giving it all up to escape almost certain death, starting again with a young family in New Zealand in the 1940s, and working in near anonymity for the next thirty years, and through all those years, continuing to create remarkable work. That is the story of Henry Kulka.

His few remaining buildings in New Zealand show him responding creatively to the new land he encountered, at the very beginning of its own awakening to modernism. They also show Kulka’s extraordinary sense of craft and refined spatial sensibilities, despite the new material challenges he faced. New Zealand, by something of an accident of history, became a key custodian of Adolf Loos’s legacy. There is still time, but only just, to secure what remains for future generations, and to awaken public appreciation of this fascinating, highly cultured and immensely talented architect.

Three houses in Remuera

Kulka built at least three houses in Remuera.

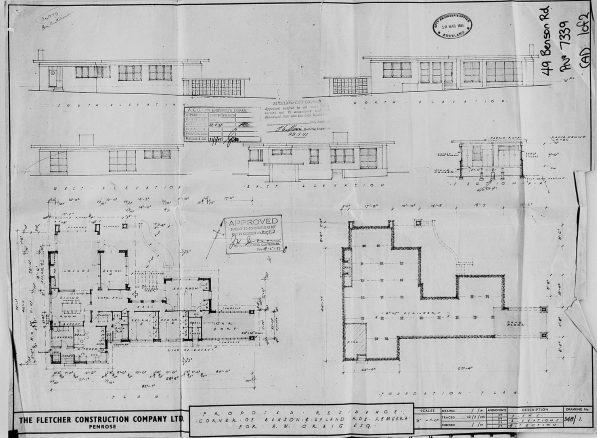

49 Benson Road, Remuera, 1950 – 52.

Of the three, 49 Benson Road is Kulka’s best known and certainly best preserved. It was published on the front cover of the July 1953 edition of Building Progress.[6] More recently it featured in the July anniversary edition of New Zealand House and Garden, 2019[7].

The site was part of a two-and-a-half acre site purchased in 1950 by Fletcher Holdings Ltd. Alex Craig, at that time General Manager of Fletcher Construction Company, bought half an acre. According to documents held by the current owner, Craig drew up the original draft plan of the house after a trip to look at modern construction methods in the United States with J.C. Fletcher. The Craig family moved into the house on 15th March 1952, and lived there until 1972. By this time, Craig had worked his way up the company to become Chairman of Fletcher Steel.[8]

The strong horizontal emphasis of the roof, the chimney projecting through the roof, the use of stone and brise soleil all recall the work of American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, and conceivably connect the house to that American road trip. The Hinuera and Putaruru stone detailing reappears only a few years later, in the stone-clad Fletcher managers’ houses in Kawerau which Kulka designed in 1955[9]. Internally, precisely laid out parquet flooring and the stone clad fireplace with abstracted keystone, are characteristic of Kulka’s work. In the main living areas, ceiling cornices merge into curtain pelmets. These have highly stylised plasterwork, with fast repeating indents, between which run wave patterns, terminating in shallow dentils. The plasterwork is original, as can be seen in the photos reproduced in Building Progress. Yet, while Kulka never simply abandoned classical detailing, it is unusual to see him deploy decoration, especially in such a highly stylised manner. These mouldings, together with the thin transomed, horizontal emphasis to the windows, and the high sheen floor, give the interior an almost 1930s, Moderne feel.

The house at No. 35 Benson Road, a few doors down the road, displays certain external similarities with No. 49. It was also designed and built by Fletcher Construction, around 1950. According to the present owner, it featured in the March 1953 issue of Australian House and Garden and was originally owned by Mr and Mrs H A Lutz, who were both from the United States. Mr Lutz also is understood to have worked at Fletchers. However, other than this Fletcher’s connection, there is no evidence that this work was also by Kulka.

Birks House, 16 Darwin Lane, Remuera, 1964

The house for Mr. und Mrs. Lawrence Birks, Remuera, dates from 1964. It is a late work, designed four years after Kulka had retired from Fletchers and was one of Kulka’s largest private houses.

It sits down Darwin Lane, overlooking Orakei Basin, just a short walk from Benson Road. The lane, which is a private road, has long been a place to discover some of Remuera’s most interesting modern architecture. Claude Megson, for example, early in his career, designed a large apartment scheme for apartments for Bill Cocker here, although it remained unbuilt. Later, in the 1960s, he designed a small house for the same client, known euphemistically as ‘Bill’s Shack’ which remains today, but is much altered. Megson also designed Cocker an experimental one-bedroom house just behind his house. It was built and then lived in by Auckland University architecture students.[10] Tony Greenhough and wife Jo, of Newman Smith and Greenhough, architects of the Wanganui War Memorial, 1960, had a slow slung modern house which once sat just below the Birks House.

The Birks House featured in the long-running Czech television series Šumné Stopy. In this series, architect and media personality, Davida Vávru, travels the world to see the work of Czech diaspora artists and architects. It has featured other Czech emigrees to New Zealand, architects Imi Porsolt (1909–2005) and Vladimir Cacala (1926–2007), who both lived in Remuera, and ceramist Mirek Smíšek (1925–2013). An episode from 2019 was dedicated to Kulka.[11] Vávru stands before a Birks house that has been so extensively altered that it unfortunately gives the viewer little sense of Kulka’s intent or intelligence. Window joinery has been replaced with modern aluminium systems. Bolt fixed glass balustrades have been added to the terrace. The roof line, which was gabled, has been extended up the hill to create a mono-pitch. Kulka’s characteristic built-in joinery and plywood panelling has gone.

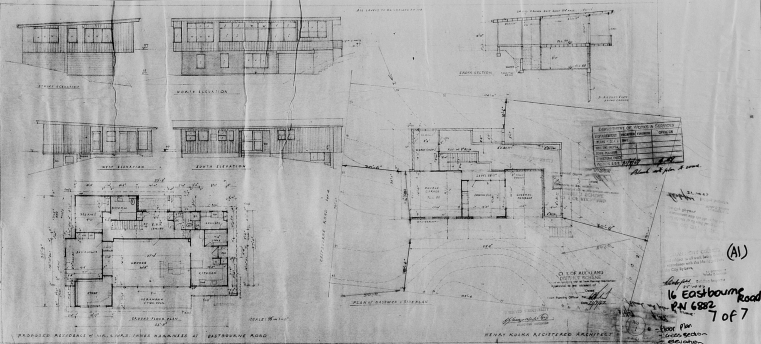

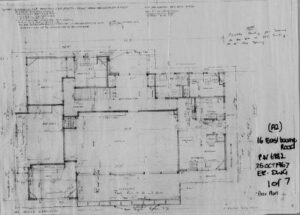

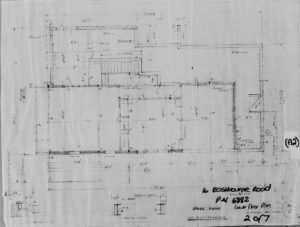

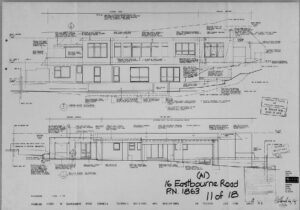

Harkness House, 16 Eastbourne Road, Remuera, 1965

The House for Billy Harkness House dates from 1965 and so again is a mature work. A view of the living room is illustrated in Richard Goldie’s 1986 Auckland University graduate thesis on Kulka [12]. This showed a plywood lined living room with seating alcove at one end. Around the room ran a high-level shelf. This would very likely have concealed up-lighting, to wash the ceiling. This feature is also found in Kulka’s Sharp House, Titirangi, 1964. The interior shows Kulka’s typical plywood panelling.

The house was altered radically during 1980s or earlier. The living room alcove was removed, and shingle tiles bizarrely added over upper floor windows. It was altered again in the early 1990s by architect Bruce Elton. His alterations were published in the journal Home and Building.[13] Although the article gave some background on Kulka and emphasized the owners’ appreciation of the house’s heritage, nonetheless most remaining visual links to Kulka were erased with this remodelling. Timber shutters and pastel plastered forms were added to create a new appearance, in tune with the period’s vogue for Mediterranean architecture, as seen, for instance, in the architecture of influential Auckland practice, Cook Hitchcock Sargisson. The Harkness House has been transformed again at least once again since, and quite recently. Today it has zinc cladding, aluminium window joinery, blond timber and porcelain flooring, white painted plasterboard and a large minimalist kitchen. The real estate literature accurately refers to the ‘slick modern living’. Despite this history of erasure, oddly, the original plan form and over volumes still remain somewhat legible. However, when recently sold, all mention of Kulka had by now disappeared from the real estate literature.[14]

Copyright – Giles Reid 03.03.23

Henry Kulka, book, available to buy directly from www.marygaudin.com

‘With images by Mary Gaudin, a New Zealand photographer living in France, and words by Giles Reid, a New Zealand architect living in England, Henry Kulka builds up a vivid picture of a methodical and rigorous architect who nonetheless imbued his work with warmth and richness. Kulka died in 1971 and, remarkably, Gaudin and Reid’s 400-page monograph is the first book to be devoted to his work.’ Jonathan Bell, Wallpaper, 16 November 2022.

Copyright Giles Reid 28.03.23