College Rifles History

In the year 1897 a military unit was formed, the original members of which were recruited from the Secondary Schools of Auckland.

The coat of arms which was adopted took the form of a Maltese Cross, in which was embodied the lion of the Auckland Grammar School, the crown of King’s College and the three stars of St John’s College. Hence the name of “College Rifles”. Colonel C.T. Major, C.B.E., D.S.O., V.D. was the organiser, and within a very short space of time he had a unit that was to make an enviable name for itself in the fields of military affairs. On the 14th July, 1897, members of the Volunteer Corps met and decided to form the College Rifles Rugby Football Club. College Rifles Rugby Club now provides playing opportunities for both senior and junior members.

Charles T Major

Charles Major, the founder of the College Rifles Volunteers, was a pioneer in many fields in the late Victorian era. Major was born in Auckland in 1869 to English parents and grew to manhood with the twin Victorian ideals of a healthy mind and a healthy body very much in place. He began his teaching career at Nelson College, where he had once been a student, and spent time in Australia before returning to New Zealand and helping found King’s College in Auckland. He was not the typical schoolmaster of his time – he did have a kindly nature and was at ease in the boys’ company – but was to have problems with politics and ambitious men later in life. Major had also been keen on military matters from a young age and in 1897 founded the College Rifles Volunteers, for ‘Old Boys of the Secondary Schools of the Colony’. He did not have much to do with the rugby club despite having been a representative player while in Nelson; other matters occupied most of his time. He served with distinction in South Africa, winning the D.S.O., and he returned with the rank of Colonel. Not long after returning from a second spell in Australia Major bought the King’s College property in Remuera but a new site was soon needed as the school continued to expand. The purchase of the current Middlemore site was hampered by World War I, in which Major again served with distinction, but was eventually completed in 1917. The many pressures associated with the war and the new college took their toll of Major’s health and for a period in the early 1920s he was not a well man. He resigned the Headmastership in 1926 but still had many problems with the Board of Governors – despite having left his teaching position Major was still the college’s biggest financial player – and often needed the help of Harry Dawson to resolve matters. By the early 1930s Major had withdrawn from the school’s affairs and he died in 1938. Three of Charles Major’s creations – King’s College, King’s School and College Rifles – have become Auckland institutions.

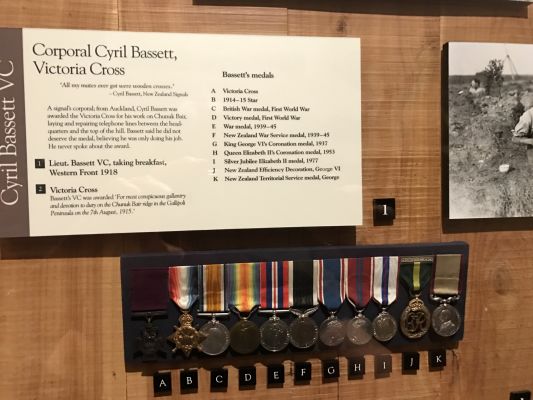

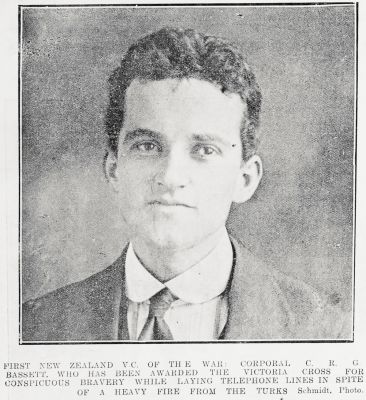

Cyril Bassett, VC

Ask most people how many New Zealanders won the Victoria Cross, the highest award for bravery available to our troops, at Gallipoli and answers would probably vary from half a dozen or so to perhaps as many as 20. Those answers would be wrong; the correct figure is one. The sole New Zealander to win this award was Cyril Royston Guyton Bassett, a 23-year-old bank clerk from Auckland and a member of the College Rifles. There are two mysteries associated with this: How did so few New Zealanders win the Victoria Cross despite so much conspicuous gallantry and how did Bassett survive long enough to receive the medal from King George V? Bassett went overseas as a member of the New Zealand Divisional Signals Company in October 1914. He was one of the original Anzacs and was still there, relatively unharmed, when the battle for the Chunuk Bair ridge began in early August. The terrain was a patchwork of steep slopes and deep gullies and was extremely difficult to cross in the face of enemy fire, but whoever controlled the high ground also controlled access across the peninsula to the Dardanelles. Initially the Allies made a good advance despite massive casualties but the 860ft ridge proved far tougher. Pockets of Allied troops clung to precarious handholds on the slope but were seriously lacking in ammunition, provisions and, perhaps worst of all, cover and communications. This was where Bassett and his small detachment came in. Their job was to lay field telephone cable for the advance parties, which was a hazardous occupation to say the least. The Turks on the heights realised the importance of communications and the lines were frequently shelled or cut by rifle fire, which meant they had to be repaired in the most perilous circumstances imaginable. Bassett remained in the field for nearly three full days carrying out his duties and managed to withdraw before the Turks launched a suicidal attack on the ridge that saw them recapture all the ground recently lost and wipe out the defenders to the last man.

Bassett’s Victoria Cross was gazetted on 15 October 1915 and the citation read: “For the most conspicuous bravery and devotion to duty, on the Chunuk Bair ridge on the Gallipoli Peninsula on 8 August 1915. After the New Zealand Infantry Brigade had attacked and established itself on the ridge, Corporal Bassett, in full daylight and under a continuous and heavy fire succeeded in laying a telephone line from the old position to the new one on Chunuk Bair. He has subsequently been brought to notice for further excellent work connected with the repair of telephone lines both by day and night under heavy fire.”’

Bassett served in France between 1916 and 1918, was wounded twice and commissioned in September 1917. He spent another ten years in the Territorial Force before retiring although he returned to the colours in 1940. In World War II he held several commands in New Zealand, retiring in 1943 as Commander Northern District Signals and with the rank of Lieutenant-colonel. In 1929 the Auckland War Memorial Museum was opened and all living New Zealand Victoria Cross holders – there were only eight and one, Bernard Freyberg, could not make it to the opening – were invited to plant oak trees as part of the ceremonies. These now mature trees still stand in the grounds in front of the Museum. Bassett, who was entitled to wear eight campaign ribbons as well as the simple purple one of a V.C. holder, died on 9 January 1983 at the ripe old age of 91.

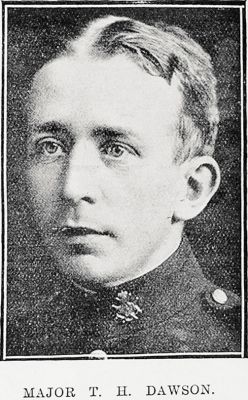

Harry Dawson

Harry Dawson was the ultimate product of Charles Major’s ideals that drove him to establish both a school and a military corps. The two men had almost identical outlooks and their careers followed strikingly similar paths. Dawson was 18 when King’s College opened in 1896 and was the first student at the new school. He was also the first Head Boy and was capable academically, talented at sport and very keen on military affairs. After leaving school he was a natural to join the College Rifles Volunteers, which he duly did. He served in South Africa with the 4th Contingent and remained here after the New Zealanders sailed for home, taking a commission with the famous Border Regiment. After returning to New Zealand Dawson soon became the C.O. of the corps and was renowned for the excellence of the troops under his command.

Camps were a common feature of Auckland life for the various militia units that then existed; under Dawson’s tutelage College Rifles won many prizes for skills and drills. He served in World War I and rose through the ranks as well as earning personal commendations, which included the C.M.G. and the C.B.E. A lawyer by profession, Dawson was responsible for drawing up the Memorandum of Association necessary for King’s College to become a Public School and later was instrumental in smoothing over troubles between Major and the Board of Governors at the school. He became the commander of the Auckland Regiment in 1932 and resumed his wartime rank of Lt-Colonel; during World War II he had a command in the Northern Military District. Dawson was also an active member of the rugby club and, in 1920, was elected its first Life Member. In the early 1950s, when such huge efforts were going into establishing a permanent home, few moves were made without Dawson’s advice first having been obtained. He dedicated much of his adult life to all aspects of College Rifles and both the rugby and military organisations had much to thank him for. Dawson died in 1956 after a long illness, shortly before the Diamond Jubilee.

Harry Frost

Harry Frost was a Canterbury man who made a lifelong contribution to rugby, originally as a player over a 12-year career that saw him represent his province 39 times and make one appearance for New Zealand, in the 1896 match against Queensland at Wellington. He was a hooker in the old 2-3-2 scrum and by all accounts a rugged and effective all-purpose forward. He moved to Auckland in 1902, just as his playing career was coming to a close, and soon he was one of Auckland’s leading referees. He became President of the Referee’s Association following a serious dispute in 1909 and holding the post for four years before retiring as a Life Member.

He worked long and hard in College Rifles’ cause, both as a committee-man and also as senior coach. He took the seniors to a playoff in 1918 and then the title in 1919, when his team played an open, fast-paced style of rugby that thrilled crowds and won matches by big scores. Perhaps his biggest contribution to Rifles’ well-being was made in the 1930s, when he argued against the club’s demotion in a restructuring of the Auckland competition; had he failed the club could well have slid into oblivion. From 1915 to 1945 he was a member of the Auckland union management committee and was its chairman between 1920 and 1934. He was made President in 1935, holding the post for a decade, and was made an Honorary Life President upon his retirement from active administration, an honour that remains unique. He was already a Life Member of the Union, having been made one in 1929. When the Frost Shield was donated for schoolboy competition in the 1930s, an elderly gentleman would be seen on the touchlines at Eden Park come rain or shine. It was the man for whom the shield was named, watching over another generation of emerging players. At national level he eventually became President of the NZRFU in 1924-25; his term coincided with the tour of the famous Invincibles. In 1939 he was made a Life Member of the national body, only the third person and first former All Black to receive the honour. Harry Frost died in Auckland on 6 July 1954, at the age of 85.

Stan Kirk

One of the legendary figures of post-War Auckland rugby, Stan Kirk came to Auckland from Wellington and was a good enough halfback to get two runs in the blue and white hoops, one in the firsts and one in the Bs. He played for Rifles over more than a decade despite some nasty injuries and by the time he was finished on the field he was already a busy man off it. Kirk became the ‘Mr. Fix-it’ of College Rifles. There are many notes in the minutes from the 1930s that: “The matter was left to Mr. Kirk to deal with.” This he always did, never failing to get an advantage for his beloved club if one was available. He coached the seniors for a while but pickings were lean and did better with the Third Grade team, while he was also Club Captain and the delegate to the Auckland union.

When World War II broke out Stan volunteered immediately, only to be turned down because he was employed in essential industry (he worked for Shell Oil and had to meet all inbound tankers, as well as playing an important part in fuel distribution in this country). Instead of serving overseas, Kirk began serving the club members who were actively facing the enemy. He took it upon himself to maintain lists of club members in the forces, where they were, what promotions and decorations were won and noting, always with sadness, those who had been killed. The toughest of all entries made on his ledger was to note that Jack Kirk (his brother) was killed at Sidi Rezegh on 29 November 1941, but the notation is made in the same firm hand as all the others. Having written the letter to the Auckland union in 1941 stating that the club would have to go into recess for the duration as all but two playing members were now overseas, Stan began writing to Rifles members on a regular basis. He penned at least two letters every lunchtime and marked the back of each envelope with a foaming tankard of ale; the return letter always had an empty glass with froth in the bottom signifying that a toast to absent friends had been drunk. He kept every reply, some 2000 in number, and in the post-War years these were invariably brought and read every Anzac Day. In time they became rather tatty and to preserve these special items the club had them copied and bound in 1988, with the originals remaining in the family’s possession (Stan had died four years earlier) and copies were held by the club and the Auckland Museum. Few of Stan’s original letters have survived but every reply was included in the four-volume set.

After hostilities ceased the club wanted to repay Kirk for his outlay, which was considerable, but he would not hear of it. Rather than argue the point it was decided to make him a Life Member, which he was pleased to accept although there was one dissention in committee (S. Kirk, Esq) that prevented the nomination being unanimous. He was a tireless and leading figure in the building programme in the 1950s and made a point of watching every team in action as often as possible, never missing any side for more than a couple of weeks. The only exception was the seniors, who he watched religiously. His wife Esther, who also gave nobly of her time to the club, learned to drive of necessity when Stan could not and always made sure he was at the appointed ground on time. The Kirk children naturally grew up in the Rifles environment and his son, Bill, was a sturdy hooker for the seniors during a 15-year career. He died in a yachting accident in 1979 when the Ponsonby Express, on which he was crewing, was lost at sea with all hands. Both daughters, Pam and Jackie, married Rifles men although they eventually had more on their minds than rugby and, while keeping in touch with and supporting the club, could never be the stalwarts their parents were. Jackie was a prominent member of the Centennial celebrations in 1997, when many of Stan’s efforts were recorded for posterity. Stan Kirk was made a Life Member of the Auckland union in 1958, more for his work with his club than for the union. It was a rare and fitting tribute to one of the game’s great personalities. Stan Kirk died on 21 September 1984 after a long battle with emphysema. Esther, who had taken her husband to matches right to the end even if he needed an oxygen tent to make that possible, died in 1994. As a visitor looks around the fine clubrooms that are the home of College Rifles they should tip their hats to the Kirks, who are truly the club’s Royal family.

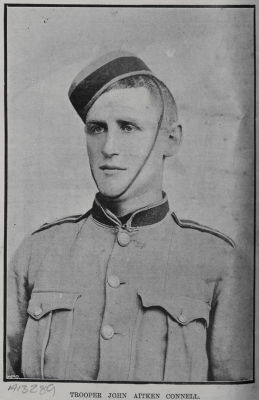

Trooper Connell

When South Africa, previously a colony of great farms, was found to contain diamonds and gold in vast quantities there was naturally a lot of interest from fortune-seekers around the world. One of the most interested was the British Governor of the Cape Colony, Sir Alfred Milner. Milner had no time for the Afrikaaners and little for the Uitlanders, the migrants, but he needed to provoke the first group into ‘starting’ a fight in which the British could be seen to be ostensibly defending the second group. This he managed to do by preventing anything that looked like settling the differences between the three groups. Eventually Transvaal President Kruger raided over the Natal border rather than sit back and be overwhelmed, so fighting broke out in earnest. Originally only Britain committed troops but after some heavy reverses shocked the British public and politicians, colonial troops were also employed. New Zealand was quick to respond and a contingent of mounted soldiers was despatched for southern Africa. The First Contingent sailed from Wellington on 21 October 1899 and was drawn from men in training with the many volunteer militia units throughout the country. The volunteers naturally had to be able to ride and shoot well, while they also had to own their own horses. Although College Rifles was not a mounted unit they were represented in nine of the ten contingents that eventually sailed. In all 33 College Rifles men served. Although the majority of casualties during what is now known here as the Boer War were from illness, disease and accidents there were still the inevitable casualties. This was the first time New Zealand had to accept news from overseas that some of its own had been killed, as it was the first occasion New Zealanders had been sent overseas to war. The first casualty was Trooper GR Bradford, who died on 28 December 1899, and the second was 119 Trooper John Vaille Douglas Connell of the College Rifles. The 23-year-old shorthand teacher was considered a steady, painstaking and excellent soldier but he died instantly when shot at Slingersfontein on 15 January 1900. A memorial to Connell, New Zealand’s second war casualty, was later erected at Mt Eden School.

1914 German Pacific Empire flag

The German flag is one of the more interesting pieces of military memorabilia in New Zealand and it has a peculiar niche in world military history. When war was declared in 1914 New Zealand was one of the more remote parts of the world but, as part of the British Empire, was expected to assist the Mother Country to the hilt. This, of course, was done at heavy cost. Early in the war, before Gallipoli and the battles in France, New Zealand was given a task closer to home. Within a day of war being declared the Governor of New Zealand, Lord Liverpool, received a telegram stating that the capture of the German wireless station at Samoa rated highly on the list of priorities. Germany at the time had a large Pacific empire stretching through Micronesia, Melanesia and parts of Polynesia, thus controlling vast tracts of the Pacific Ocean and presenting a real threat to Allied shipping. An expeditionary force of 1363 men was quickly put together and set sail for Samoa. College Rifles was well represented, as the Signals section was essential to the task. On August 29 the force reached Samoa, having missed contact with the German Pacific fleet commanded by the famous Admiral Graf von Spee, and two members of the party went ashore to deliver the ultimatum to the German Governor, Dr. Schultz. Since the country was to all intents and purposes undefended, Schultz did not stand in their way although he never formally surrendered the territory and that afternoon the New Zealanders became the first Allied soldiers to capture German-held territory during World War I.

The flag was recovered from the Governor’s house by Lieutenant Cotton of the College Rifles, who later brought it home and presented it to the College Rifles Club. Whether it was the first German flag taken – there were others also flying over the house – is unclear but it was certainly one of the first captured. It remained in possession of the College Rifles Club until that body disbanded, when it was returned to the family. It was purchased outright by College Rifles RFC in 2004 and has had a small tear expertly restored by the Auckland Museum, thus rendering this flag one of the best-preserved and most interesting artefacts from World War I.