Claude Megson’s Remuera Townhouses

Claude Megson (1936–94) was a brilliant, if controversial architect and teacher, who built five single-family houses and three townhouses in Remuera during the 1960s and 1970s. This article focuses on his townhouses. Firstly, it introduces Megson, though briefly, as biographies exist elsewhere.[1] Then it frames the main ideas informing his multi-unit designs. Finally, it gives an overview of the buildings themselves.

Remuera Heritage, 1 September 2023, © Giles Reid

I – Claude Megson

Claude Walter Megson was born in Whangarei, 29 July 1936. He was the eldest of three children born to Annie Storey, a seamstress who in later years was a nurse aid at Whangarei Hospital, and to Cecil Wallace Megson, a carpenter, who during the war years was a bridge inspector for the railways, and later became co-owner of Whangarei Builders Ltd. Claude was educated at Hora Hora Primary School and then Whangarei Boys High School. He moved permanently to Auckland around 1955, working at one of New Zealand’s foremost architectural offices Gummer and Ford while studying part-time at the University of Auckland School of Architecture. He became a senior assistant of design there and became close to partner Charles Reginald Ford (1880–1972), who famously had been a member of Scott’s 1901 expedition to Antarctica. Megson lived for a time in a small shed in the rear garden of his employer’s family house St Heliers Bay Road.[2]

Quoting from the introduction from the book Claude Megson – Counter Constructions:

[Megson] commenced private practice in Auckland in 1962, the year he graduated with a diploma from Auckland University School of Architecture. He taught at the University part time from 1965 and on a full-time basis from 1969, when he received his master’s degree. By then he had already completed some notable houses. He taught all levels of the School and lectured on the theory of design. From the early 1980s onwards, he ran first and second year design studios. He stopped teaching only a few months before his death from cancer on 8 June 1994, aged just 57. He has been cited as a major inspiration to several generations of architects, including nationally prominent figures Simon Carnachan, Patrick Clifford of Architectus and Ken Crosson as well as other now less well-known architects, such as Robert Paterson, designer of the mirror clad masterpiece at Black Rock (Takapuna, 1984)[3]

Megson’s reputation today appears strong, if an architect’s name becoming a realtor unique selling-point is any indication. That said, reputations are fragile and in Auckland they offer scant protection from unsympathetic ‘modernisation’ or at worst the wrecker’s ball. The Jopling House, 59a Achilles Point, St Heliers (1965), a key early work in Megson’s oeuvre, was demolished last year by its new owner, despite Megson’s name and the work’s architectural significance appearing prominently in the slick marketing campaign.[4]

Agent Elyas Salimi from Ray White Mission Bay says that this is one of the most exciting properties he’s ever had the pleasure of marketing. ‘It took a while to get my vendors to this point because they absolutely love the house, and interest is already intense. Potential buyers are getting all the personality and character of a Claude Megson home, with everything brought right up to date for the Code Compliance Certificate.’[5]

The particular tragedy of this house is that the previous owner had only bought the house four years earlier and made extensive, very costly, and largely sympathetic renovations. The hardwood timber and Kamo bricks (seen again in Megson’s Wong House and now impossible to procure), were simply pushed over bulldozed into a pile. Aside from the destruction of the city’s architectural heritage, issues of recycling and embodied energy should, by now, surely attract far greater attention in Auckland than they do. However, increasingly urgent environmental issues still remain marginal to the city’s speculative housing market.[6]

Megson’s improved reputation is a recent turn of events. For twenty years after his death in 1994, he was a neglected figure. In truth, in the decade prior to his death and right up until the time his cancer became known and there was a flourish of eulogies, he had largely faded from view.[7] Megson had sharply divided opinion at Auckland University School of Architecture. To half the school he was as an inspiring almost messianic lecturer. To the other half he was considered dogmatic, his ideas of domestic roles of men versus women jarred with many and he was completely out of step with the post-structuralist theory and more laissez-faire teaching methods of the department. The days when his architecture was an active part of the conversation were seen by most to be well behind him.

Megson’s peak years spanned from late 1960s right through the end of 1970s or into the early 1980s. In the mid-1970s, occupied the same architectural pantheon as Ian Athfield (1940–2015) and Roger Walker (1942–), Peter Beaven (1925–2012) and John Scott (1924–1992). In 1972, the quintet exhibited as the coming new wave, at the Dowse Art Museum, Lower Hutt, in a show entitled The New Romantics. However, despite each of the other four architects having their own barren patches, none of their fortunes ever dipped afterwards as did Megson’s. For instance, Walker’s status today in popular journalism remains high, even though it is based almost entirely on the output of his early career.

II – Ideas Informing Megson’s Townhouses

Megson applied the same level of rigour and experimentation to his townhouses as he did to his single-family homes. There are three Megson townhouses in Remuera: the Mrkusich Townhouses (1969), the Germann Townhouses (1970) and the Rees Townhouses (1974). Outside of Remuera, there are a further three buildings. Megson’s best known work is the Cocker Townhouses, 57 Wood Street Freeman’s Bay, 1973–77, for siblings Bill and Finola. Megson designed four units at 120 Lake Terrace, on the shore of Lake Taupo, 1984. The developer erected just one, which still exists but has been altered beyond recognition. Megson’s final realised work was for three apartments at 7/79 Shelly Beach Road, St Mary’s Bay, c.1992, prominently sited above Westhaven Marina.

- Medium Density Housing

Megson’s work stands as an early exemplar of inner Auckland, medium-density, low-rise housing. He showed particular skill in working on difficult sites and taking advantage of planning regulations to achieve unit numbers which proved attractive to a developer. These abilities presumably offset in the developer’s minds whatever initial doubts they must have harboured over the perceived complexity and cost of his designs.

Medium density housing as a building type pre-occupied Auckland architects during the 1970s. The beginning of the decade saw widespread destruction of the inner-city’s heritage, a process which only accelerated in the 1980s. The expansion of the motorway system had shattered the suburb of Grafton in the late 1960s, leaving a permanent scar on Auckland’s landscape and its psyche. There was increasing awareness that the central city was becoming a monocultural business ghetto, where nobody with any means would choose to reside.

Opposing this trend, emerging Auckland architects pushed back with a debate on the merits of multi-unit infill development. This housing type was seen as one way of bringing life back to the inner suburbs and meeting the needs of a growing population without rapacious land use.[8] Alongside this, there stood the desire to preserve Auckland’s historic landmarks and the innate character of its established suburbs.[9] Architects, it was not unreasonably put, had the training to respond creatively to awkward, land-locked sites, often surrounded by historic buildings. It is salutary to realise just how long these debates have existed in this city.

The Auckland Architecture Association (AAA) Bulletin, a progressive and politically active journal, provides a good insight into the thinking of the period. It regularly gave prominent coverage to multi-unit housing. During the 1970s, judging by this journal at least, the single-family house, today the mainstay of New Zealand architectural publishing, was viewed as an area of limited social and artistic importance. Megson’s work often featured in the Bulletin’s Monier Award editions (later Cavalier Bremworth, later AAA Awards), and he won several awards, in no small part due to his exceptional graphic skills, which set him apart from his peers.

It is curious to note how much of the Auckland multi-unit work featured in this journal has slipped from contemporary conversation. Potentially this has contributed to a skewed history in which the era’s architecturally designed apartments have come to be seen as the preserve of architects further south; specifically, Athfield and Walker in Wellington, Beaven, Warren and Mahoney, and Don Donnithorne (1926–2016), amongst others, in Christchurch. Forgotten examples of multi-unit housing, located near to Remuera, analysed in the AAA Bulletin include:

- Hill, Manning, Mitchell’s Coles Apartment, Alberon Street, Parnell, c. 1972 (demolished and from the published photos, of obvious architectural interest)[10]

- Peter Stenhouses’s five townhouses on the corner of William Pember Reeves and Arthur Streets, Freeman’s Bay, 1972[11]

- Sheridan Lane, Freemans Bay Scheme A by Dempsey, Morton & Co. and scheme B by Angus, Flood and Griffiths, 1973[12]

- Gillespie, Newman Pearce, Scarborough Terrace, Parnell, 1976[13]

- Epsom Mews, 533 Manukau Road, Epsom, 1976, architect un-named and unknown to the author.[14]

- Colonial Vernacular

A second idea operating throughout Megson’s work is the colonial vernacular. Its appearance is overt in the Germann and Cocker Townhouses. It reappears strongly in his late work from the mid-1980s on, such as the Morris House, Auckland Road, St Heliers (c.1991). While Megson’s architecture from the 1970s is better known today, an assessment of his rarely, if ever, published output during the 1980s and 1990s is long overdue.

Megson’s Remuera townhouses date from a time when New Zealand architects were exploring the country’s colonial past, its pitched roofs and verandas, timber ornament and weatherboards. Other Auckland architects investigating the vernacular included Simon Carnachan (subsequently of Fairhead, Sang and Carnachan), Peter Cavell (who later emigrated to England), Cook and Hitchcock (pre Sargisson), and Hunt and Reynolds. Slightly preceding them all was academic and architect Peter Middleton (practising in Auckland 1950–65).[15]

The colonial vernacular offered a clear alternative to international modernism, which was fast running out of steam as the decade wore on. Later, during the 1980s, this concern with the reuse of history would transmute into a strain of International Postmodernism in the work of Athfield, David Mitchell (1941–2018), and Walker, before seeping into the larger scale commercial and institutional work of Warren and Mahoney and Auckland practice JASMaD (Jelicich, Austin, Smith, Mercep and Davies, out of which arose JASMAX in 1989). Megson was one of those rare New Zealand architects who did not take this turn and held out against the postmodern movement. This principled stand unquestionably hurt his currency then, although it has given renewed impetus to it since, certainly amongst a younger generation.

- Everyday construction

Megson typically designed with the everyday New Zealand materials of 1970s modernism such as unpainted concrete masonry and Brownbuilt (long-run, metal-tray) roofing. Megson and his employees obsessively redrew the guttering, door and window junctions typically at one-quarter and one-half inch scale details, to describe clean geometric profiles and shadow gaps Megson sought. His designs, regardless of the budget or scale of the project, were dimensionally exact, lacking slack or adjustment, such as traditional mouldings or more conventional New Zealand timber stud framing can provide.

Only the most resolute of contractors could build these works. His multi-level foundations, to name but one element, required an inordinate amount of time-consuming setting out and checking. Neil Jessiman was the contractor for nine of Megson’s houses: the Barr, Bowker, Donovan, Lowe (location and date unknown), Mayes, Norris and Wong houses, and the Germann and Rees Townhouses.[16] Clearly the relationship between architect and builder was successful. However, one can only wonder how Jessiman can have made any profit from executing these maddeningly precise designs.

- The room as building block

Both Megson’s townhouses and houses are characterised by partially bounded rooms, each with their own identity, often with their own individual roof. These rooms, which can seem minute by today’s standards, are offset in relation to each other in plan, forming linked volumes, pathways and diagonal views, expanding the eye out to other rooms, and beyond these to the edges of the site. Place sufficient rooms together, with full attentiveness to their outlook, orientation and the rituals they contain, and one creates ‘architecture’. It was this method of aggregation with which Megson instructed generations at Auckland University.

However, despite Megson’s refusal to examine the formal composition of his own work with his students, there are plainly far more sophisticated formal ideas at play than merely putting one thing next to another. In its intricacy and delight in the small scale, Megson’s architecture has often been joined to discussions of Athfield and Walker’s architecture. However, in its geometric rigour and psychological intensity, his work is in most respects, far apart. There is never any sense of ad-hoc growth and adaptation in Megson’s work, as there is in Athfield and Walker and in Beaven’s work as well. Nor is there that complicit awareness that as a New Zealand architect, you should adopt the guise of the larrikin, or ‘good keen man’, to mask one’s artistic goals. Instead, a specific, ambitious and clearly High Art geometrical investigation underpins every move in each project. Through the 1970s, his designs became interlocking three-dimensional puzzles of ever-increasing spatial and formal complexity, which still astonish today.

- The garden as room

The room, with its bed, dining table, or bath, is the basic building block of Megson’s houses. However, the room does not stop at the walls of the house but continues out into the garden. Megson overlaid the entire site with a pattern, described by concrete masonry retaining structures, as well as hedging, paving and terracing and careful planting. These lines commandeer the land, inviting occupation.

His sister Colleen Cooper recalls that:

Claude’s main hobby was gardening, at primary school he always won the yearly garden competition. In his last two years of high school, he worked in a market garden in the weekends.[17]

This idea of the ‘garden as room’ goes back, certainly in the modern English landscape tradition, to Vita Sackville West (1892–1962) at Sissinghurst, near Cranbrook, Kent. More pertinent for Megson however, might be to reflect upon the designs of Gertrude Jekyll (1843–1932), starting with her own garden at Munstead Wood, near Godalming, Surrey, c. 1896 onwards. Munstead Wood was Jekyll’s first collaboration with a young (later Sir) Edward Lutyens (1869–1944).[18] The house, unusually, came after the garden, in 1909.

Whether Lutyens was as yet a direct influence on Megson in the 1970s is a matter of current conjecture. Robert Venturi (1925–2018) led the reappraisal of Lutyens in his 1966 book Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, so in terms of timing, one could make the argument. The wider professional and public re-examination of Lutyens however did not begin until the pivotal 1981 exhibition Lutyens: The Work of the English Architect at the Hayward Gallery. Lutyens would become an overt reference for Megson during the mid-1980s onwards.[19] This is seen most clearly in the richly textured materials of Megson’s own home at Fern Glen Road, St Heliers, 1983, mixing red brick and quarry tile, timber shingles, patent glazing, stainless guttering and painted mild steel wire mesh and railings. It is here that Megson fully assumed the grand tradition of the Auckland Arts and Crafts house, particularly those by Roy Keith Binney (1886–1957), whose houses still grace Remuera.

During the 1980s, Megson designed two large-scale landscapes in Remuera for houses which he did not design. Both houses still exist, however neither garden design, it is believed, was ever realised. One was for Sharon and Bruce Prichard at 3 Eastbourne Road, a grand colonial building. The other was an extraordinarily ambitious design for merchant banker David Richwhite of Fay Richwhite, at 542 Remuera Road, where sits a house originally designed by Binney. Megson’s protégé, Robert Paterson, later altered it, with his new work replicating Lutyens’s Deanery Garden, Sonning, Berkshire, 1899–1901.

- Environmentalism

Megson designed rooms for living and dining, both informal nooks and more formal settings, places to sit at various times of the day and night, allowing one to follow the sun in search of warmth and light. In all of his work, there is the sense of camping out across the house. He asks the owner to seek out the most comfortable perch in order to perform their rituals of bathing or sleeping, cooking or relaxing. This approach now looks very forward environmentally. It was only in the 1980s, well after the oil shock of 1973 had receded, that it became the New Zealand norm to design large, open-plan spaces, extensively glazed and with limited shading, where (then) cheap energy would temper the environment.

The multitude of spaces in Megson’s houses was born of a deep interest in human psychology. His thinking shared affinities with the anthropological writings of Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908–2009), as well as aspects of Dutch Structuralism, specifically architect Aldo van Eyck (1918–1999). Van Eyck lectured in New Zealand in 1964 and was a key influence on Megson’s philosophy, if not his actual forms. One of van Eyck’s major ideas was that architectural form should be derived from the close study of the actions, rituals and patterns of its occupants, and that to a very real extent, architecture was a science.

This methodology took hold at the University of Auckland School of Architecture in the 1970s, in the teaching of Professor Peter Bartlett (1929–2019, retired 1993), Professor John Hunt (who taught papers on van Eyck and Herman Hertzberger), as well as Megson himself. These ideas were still influential on the curriculum up until the mid-1990s. The encouragement to drift out across the whole house, nomad-like, was advanced by another interesting but rather forgotten architect, Nigel Cook, in the Kelly (Wind Rain) house, Paraparaumu, 1988. In subsequent works, Cook even set out to measure and monitor the environmental performance of his houses using data collected by computerised sensors. Cook is not an obvious descendant of Megson, but both, in their own way, sought to re-awaken users to the vagaries and pleasures of the environment.

III – Megson’s Remuera Townhouses

Mrkusich Townhouses, 64 Hapua Street, Remuera, 1969

It would be difficult to find a road in Auckland of comparable size to Hapua Street with as many architect-designed houses.[20] The lower, flatter terrain, say up until around No. 40, largely consists of state housing. This looks set to change, with the arrival of RTA’s black and white clad ‘Family Pavilions,’ 2021, whose blank-ended gable forms starkly proclaims the coming gentrification.

The cul-de-sac was probably extended up into the valley in the mid-1960s.[21] This accounts for the change in character about two-thirds of the way up. Here, virtually every other house is standout work by a prominent modern Auckland architect. The list of architects’ houses on Hapua Street includes:

- 54, Rees Townhouses, Claude Megson, 1973

- 58, Ron Sang’s house, 1973

- 73, Bill Wilson (Group Architects), 1967

- 74, Geoff Newmann, 1963

- 76, Chrystal House, Lillian Chrystal, 1969 and

- 78, Richard George, of Stephenson and Turner, 2007.

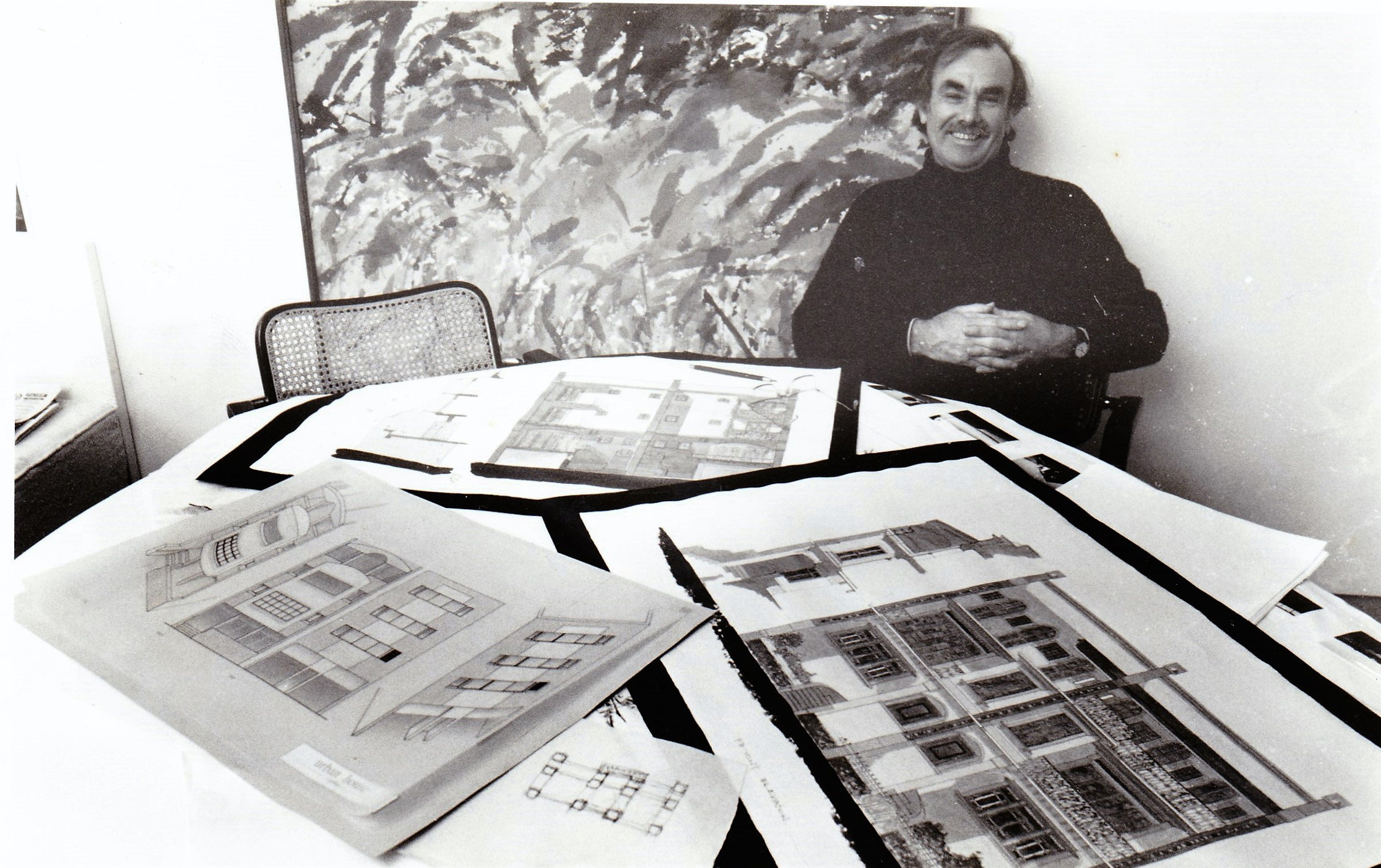

Megson mixed in artistic circles. His circle of clients grew to include Elam School of Fine Arts graduate Pat Barr, Bill Cocker, keen collector of artists Ralph Hotere and Richard Kileen, artist and graphic designer Roy Good, Gavin Rees, owner of the ‘Design Store’ and Jan Todd, who also trained at Elam. Megson was gaining a name as the go-to architect for those willing to patronise radical architecture. Artist Milan Mrkusich (1925–2018) and his wife Florence (1926–2015) had designed a house for themselves in 1951, off Arney Crescent during Milan’s days at Brenner Associates.[22] The Mrkusichs subdivided the bottom of their site and commissioned Megson to design them three townhouses on it. One can just glimpse the Mrkusich House from the top end of Hapua Street.

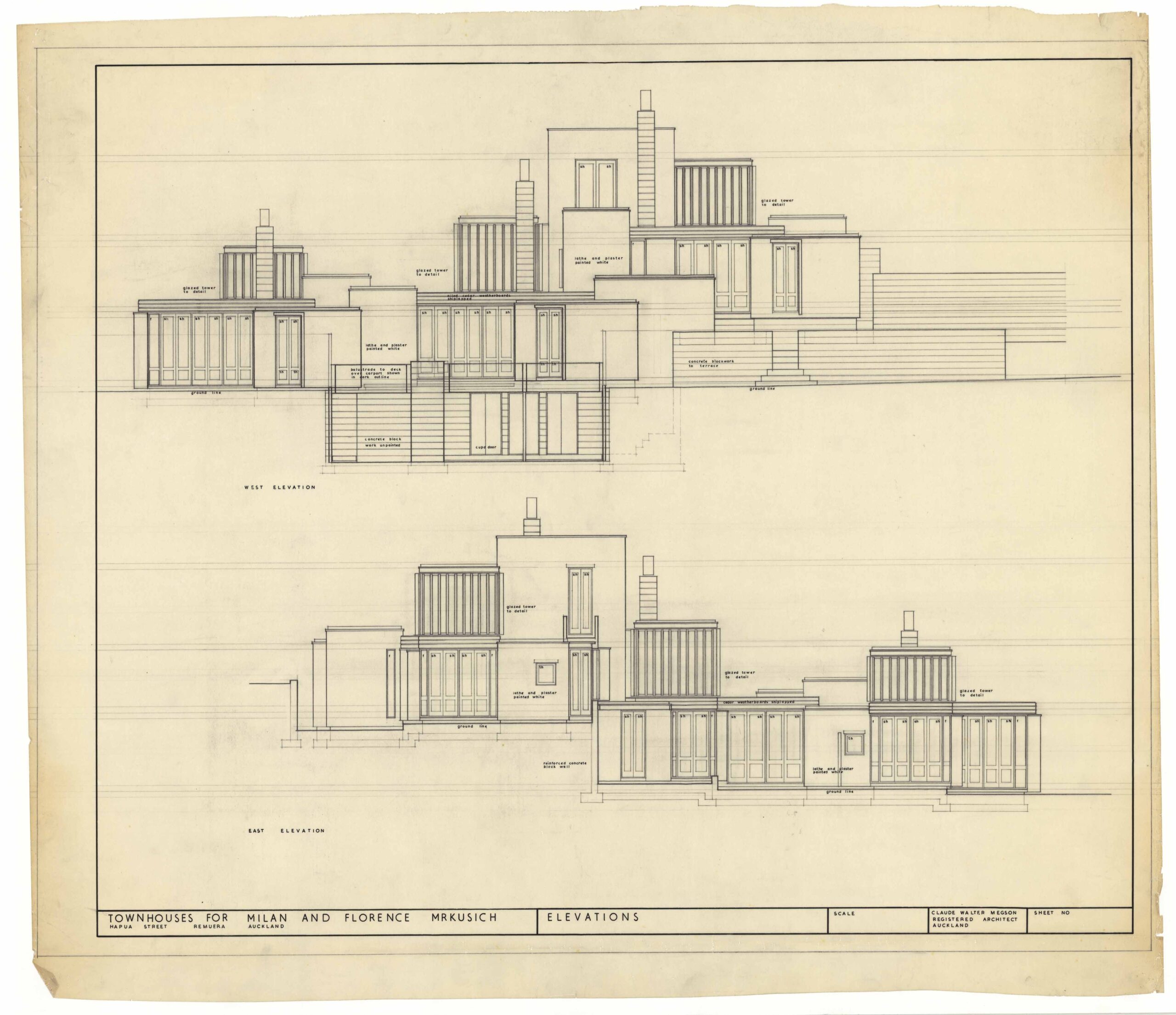

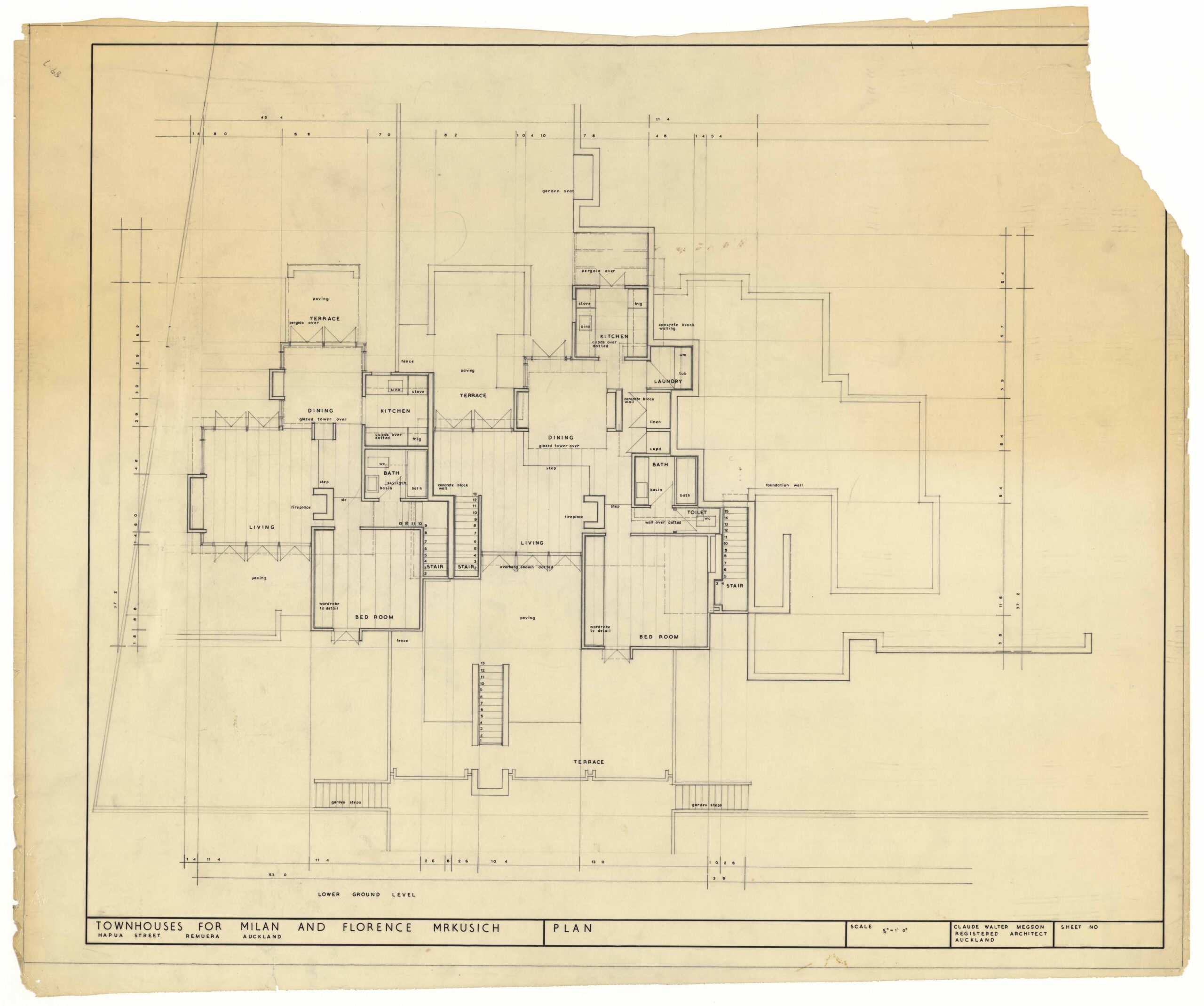

Externally, the Mrkusich townhouses feel like the beginning of a shift away from the compositions Megson had mastered in recent works – diagrammatically expressed in the Wade (1963) and Jopling (1965) Houses, and dramatically seen in the Wong House, Remuera (1967). In these three works, each room is expressed as a flat-roofed box, held together by strong axes of symmetry. However, the Mrkusich Townhouses do not cohere into a singular image in quite the same way, but rather hint at Megson’s increasing efforts to break free from the Beaux-Arts training he acquired working at Gummer and Ford. From the late 1960s on, Megson’s compositions deny symmetrical relationships between the various parts of the plan and elevation.

Immediately after the Mrkusich Townhouses, Megson pivots away from an assemblage of cubes altogether, with forms jostling over the slope, towards an exploration of quick-change pitched roofs. This evolution first appeared at the Good House, Oratia, 1968, and then shortly after was used again at the so-called Bill’s Shack, Darwin Lane, Remuera, 1970, for Bill Cocker. Pitched roofs allowed Megson to create a dance of forms over the platforms below and to explore diagonal relationships in section, as well as in the plan.[23] They also allowed him a better chance of keeping out Auckland’s heavy rain. Notoriously, Megson’s projects could experience roof failures, later resulting in costly, prolonged and painful repairs by his clients.

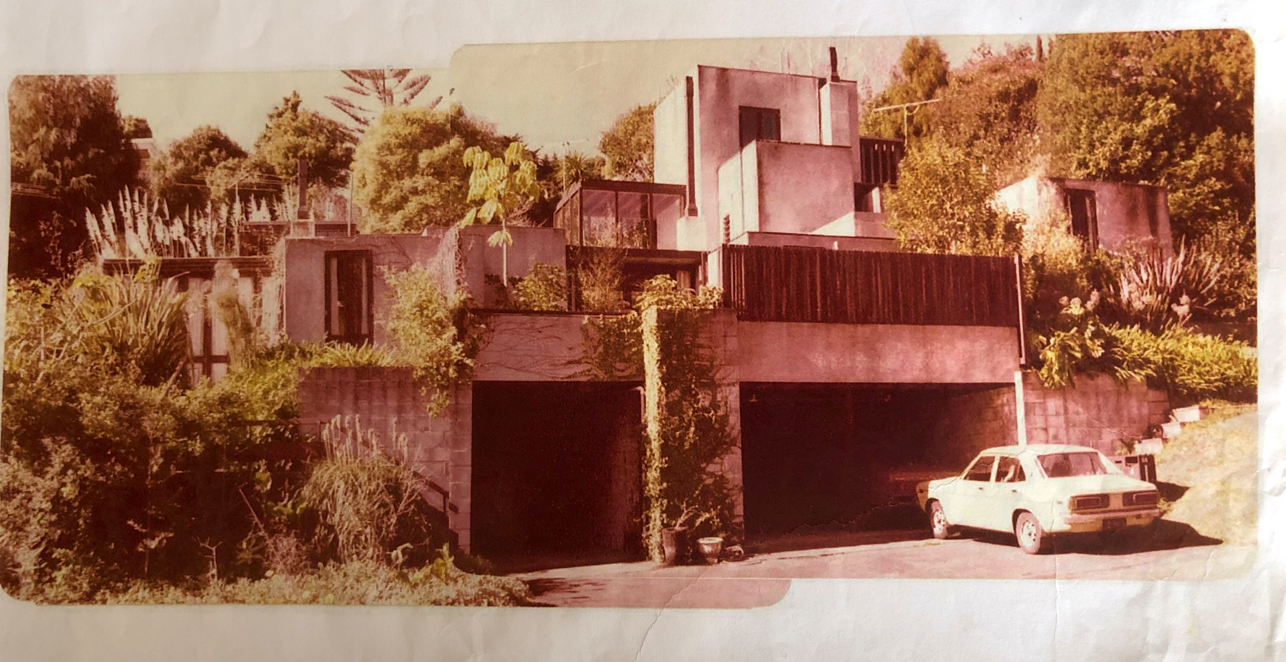

Construction difficulties and cost overruns beset the Mrkusich project. Client and architect fell out badly. Milan remained unwilling to discuss Megson until the end of his life. By the 1990s, the apartments felt tired. Various owners had attempted ad-hoc methods to stem leaks from the naïve flat roof details. The latter part of the 1990s was the low point in Megson’s standing. Today the turnaround in their fortunes, as well as his, is unexpected and largely positive. The Mrkusich townhouses reveal themselves to be a collection of liveable and attractive, if tightly planned spaces, suitable for a young couple or single occupant.[24]

Architect Lisa Webb began this trend with her alteration of No. 3/64 Hapua Street, the uppermost unit, in 2005.[25] Webb has a more ambitious work close by, her renovation of the aforementioned No. 74 by Geoff Newmann, in 2014.[26] More recently unit 3’s chimney has been removed. The other two apartments were purchased separately in 2011. Both owners chose to keep the stained timber unpainted and in this, they have sought to maintain more of the work’s original feel. The units were designed to sit above carports, with the entry through the rear, from where one rose up steep, narrow stairs into the house. Two carports have been converted to garages and the entry placed outside.[27]

The design is notable both for the compact size of its rooms and how it counters any impression of smallness. The bedroom opens off the living space.[28] A free-standing concrete block fireplace anchors the living room. Megson designs it with tall flue and squat base, its totem-like character reminiscent of Louis Kahn’s chimney at the Margaret Esherick House, Philadelphia, 1961. The dining area is located beneath a timber-louvred glass lantern of similar height to the space below. This adds a strong vertical dimension to the main space and brings light into the heart of the house. The building nestles into the hill and the interior would otherwise fail to receive light from the east. Off of this space is a galley kitchen, with the bathroom beyond. The units have external courtyards front and rear, again room sized. These courtyards extend the interiors out into the garden and bring necessary relief to the townhouses’ small dimensions. The theme of doubled courtyards, diagonally opposed, becomes a common thread in Megson’s work hereafter.

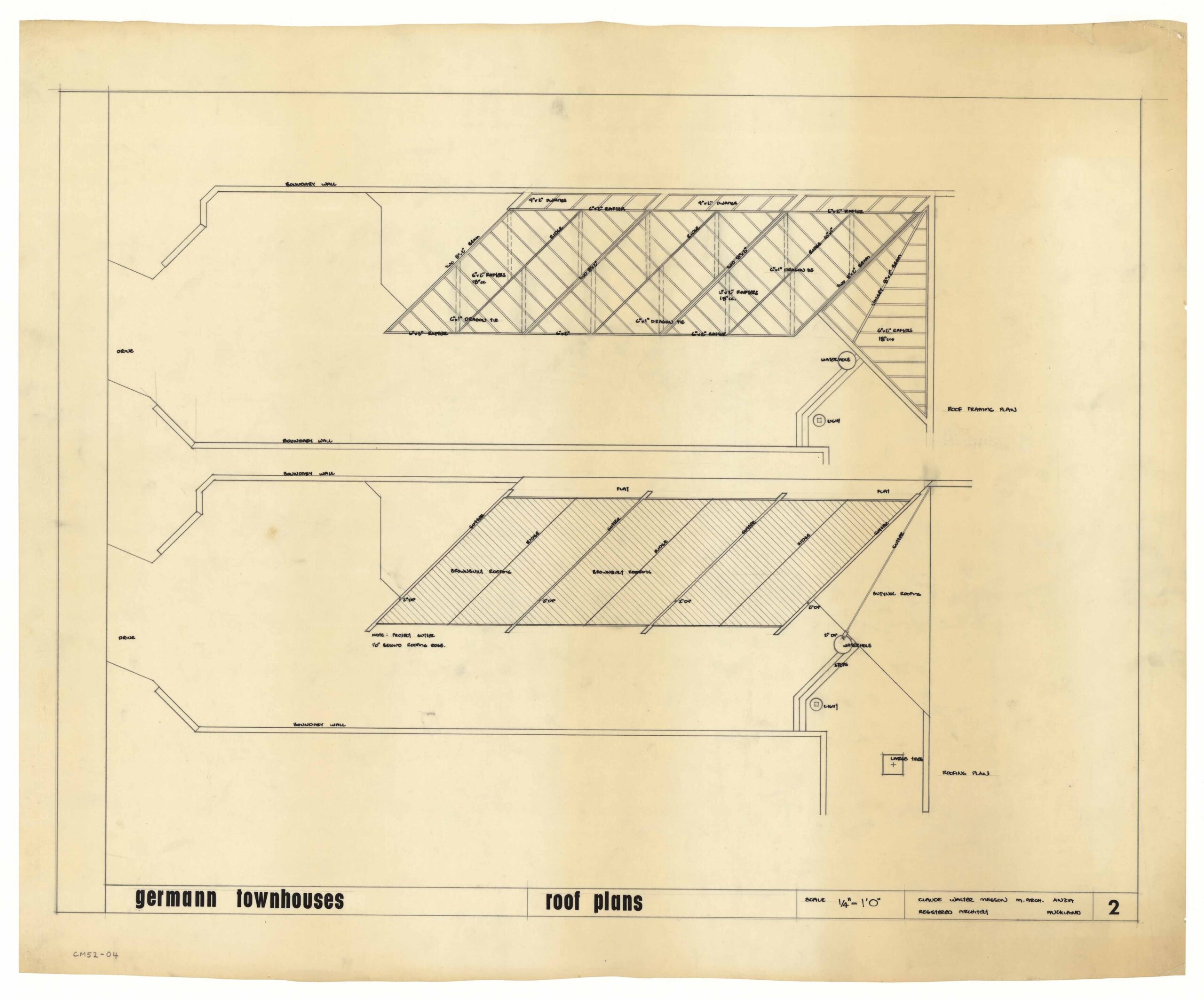

Germann Townhouses Claude Megson Collection. (CM52) Architecture Archive. University of Auckland Libraries and Learning Services

Germann Townhouses Claude Megson Collection. (CM52) Architecture Archive. University of Auckland Libraries and Learning Services

Germann Townhouses – 14a MacMurray Road, 1970

The Germann Townhouses are overlooked within Megson’s oeuvre. It is not obvious why. The scheme won an Auckland Architectural Association (AAA) / Monier Award in 1971. Megson presented a physical model. The judges were John Goldwater (1930–2000), architect of the brilliant Auckland Hebrew Congregation’s Synagogue and Community Centre, Greys Avenue (1968), and architect and writer David Mitchell with whom Megson held a lifelong rivalry at Auckland University School of Architecture. Their citation read:

These flats were considered in themselves as small flats, but were very good in terms of their recognition of the old buildings in the immediate environment built 60 to 80 years ago. The scheme showed concern for the past and aided the good buildings of this period by designing the new project in a sympathetic manner. This is in strong contrast to the current practice of bulldozing away the older environment to produce characterless machine-like productions in their place.

Were the judges alive to revisit MacMurray Road today, there would be no need for them to change that last sentence.

Megson designed the townhouses for Mrs Germann. However, construction stopped after commencing on site, due, it is believed, to financial issues. The scheme was revived by a young property student Doug Walsh, who had studied a paper under Megson at Auckland University. Walsh would, later in life, commission Black Rock from Robert Paterson (now terribly disfigured), and work with Megson again towards the very end of his life, commissioning the aforementioned apartments at 7/79 Shelly Beach Road, St Mary’s Bay, approx. 1992, which still exist.

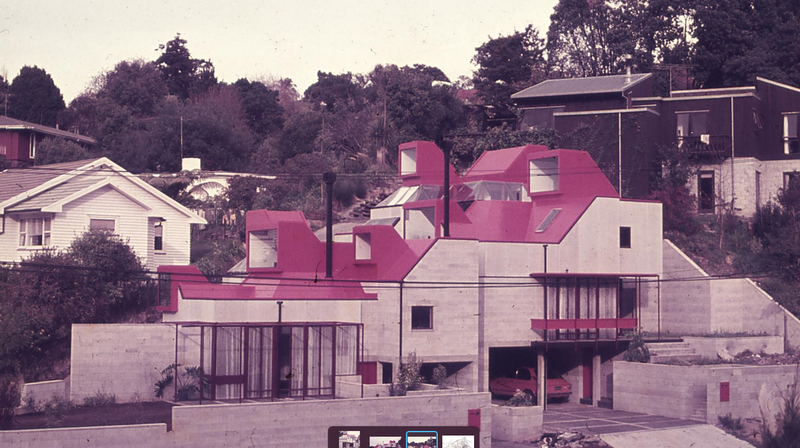

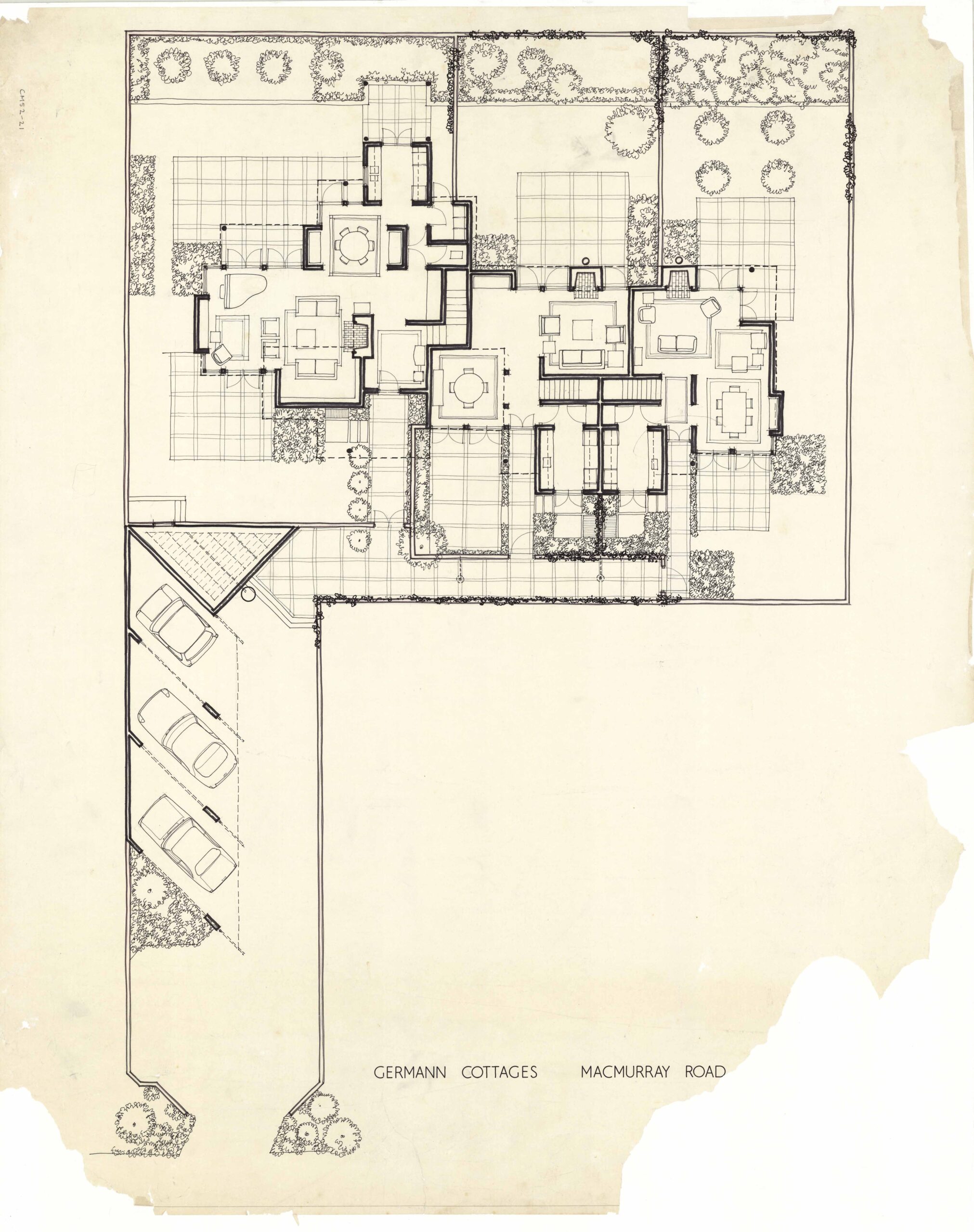

MacMurray Road runs parallel between State Highway 1 and the doctor’s clinics lining the Newmarket end of Remuera Road. The terrain is nearly flat, which is unusual to find in Megson’s oeuvre. The site is ‘L’ shaped, with a driveway running down the left-hand side of what was until recently, a large, single storey colonial villa. The irony of this contextual work is that the context it referenced is now disappearing around it.

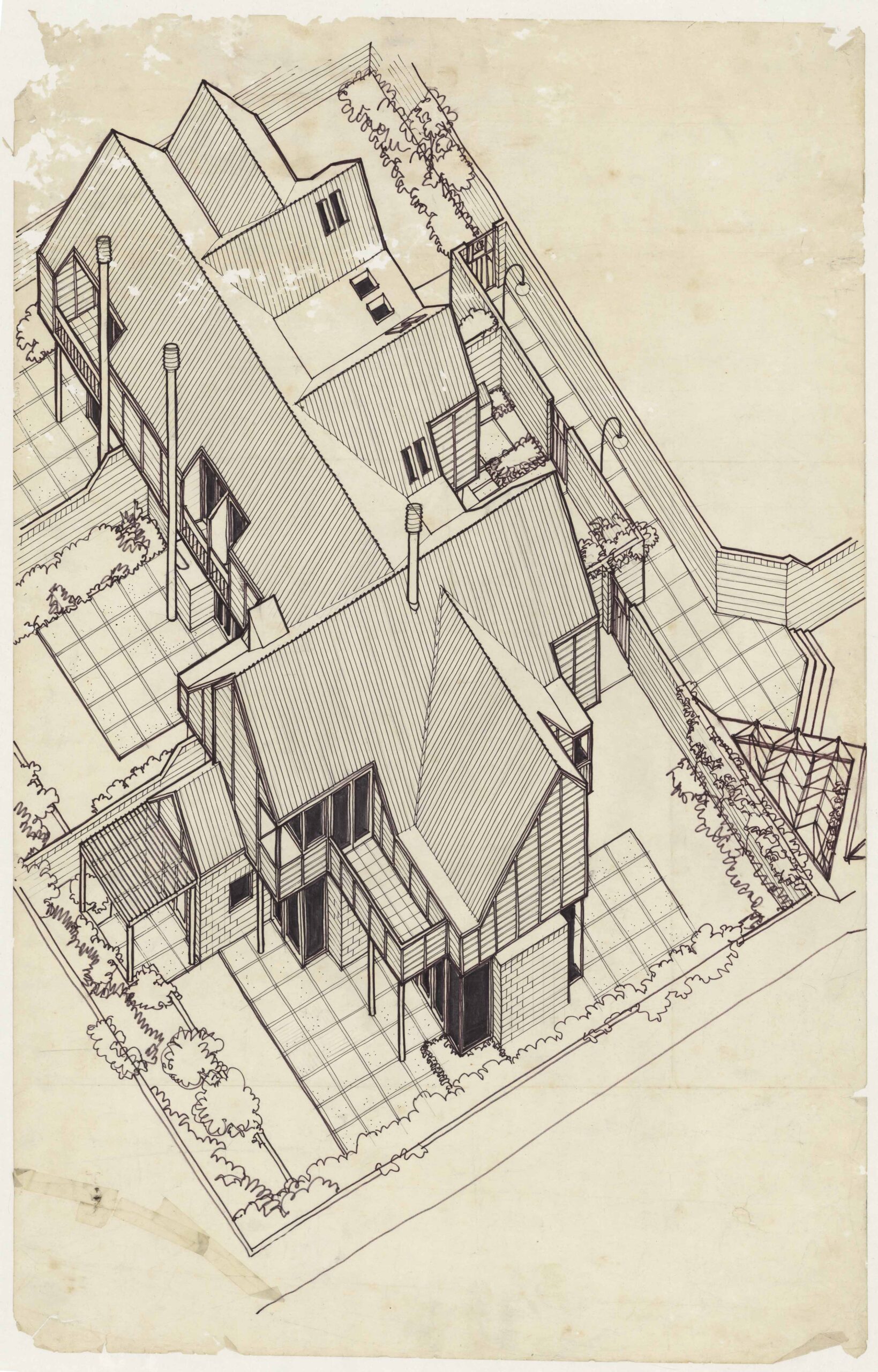

Walking down MacMurray Road, the first small sign of the architecture to come is a pitch-roofed letterbox. Something interesting begins to emerge as one approaches the three carports. Because the driveway is so narrow, it was not possible to provide right angled parking. Instead, Megson arranged the parking spaces at 45 degrees. One drives up and turns into them at an angle. One reverses to get back out. The three end gables are set parallel to the driveway, but the ridges and valley gutters are all skewed to a 45-degrees. The rhomboid roof plan results in perversely difficult-to-execute detailing. However, this single act of geometrical translation transforms what would have been ordinary construction into anything but.

At the end of the driveway and three steps up, lie the houses themselves. The largest unit forms the head of the development. A hedge-lined lane runs off to the right, lit at night by white-painted arched steel posts supporting globe lights. The footpath and planting conjure up the romantic image of a small terrace of houses, such as one might discover in the more village-like parts of London, for example the back lanes of Highgate. To enter each property, one passes through a timber wicket gate, into a small, private forecourt, and then into the house itself. On the other side lies a north facing garden.

Megson demonstrates here his particular skill at arranging the layers between public and private. The interiors to the two small units are small, though have good views front to back and look onto attractive gardens. The largest unit, which today has the most developed landscaping, incorporates a double height space, revealing the drama of the roof forms from within. The swooping rough sawn sarked ceilings, previously stained deep brown, bears close resemblance to one of Megson’s best works, the Norris House, 20 Walton Road, Remuera, 1973.

The roof plan is comprised of repeating gables. These, together with the white painted rusticated weatherboarding, give rise to the building’s colonial villa associations. It would however be simplistic to say that Megson was simply accommodating himself to some preconception of Remuera respectability as a means of assuaging the planners. To look closer at the plan of the German Townhouses is to realise that Megson repeatedly undercuts and reworks the villa reference. It is the continual transformation of a simple, initial form, towards a new form made up of multiple parts, finally arriving at a complex project-specific geometry, which sheds interesting light on Megson’s design process.

The plan is crucifix-like. Even this shape is a slightly off-kilter with any notion of historic revivalism. The crucifix is not one of the villa plan-types Jeremy Salmond identified in his landmark study Old New Zealand Houses: 1800–1940. Looking closer, one sees that ridgeline of the long gable steps slightly where it meets the main cross gable. This suggests a business or quirkiness to the layouts below, which is indeed the case. There are a further two gables fronting onto the lane. These demarcate the individual townhouses. This balancing of the traditional and modern, the representational and abstract, makes the Germann Townhouses such an insightful work in the study of Megson, and a key, transitional work in his oeuvre.

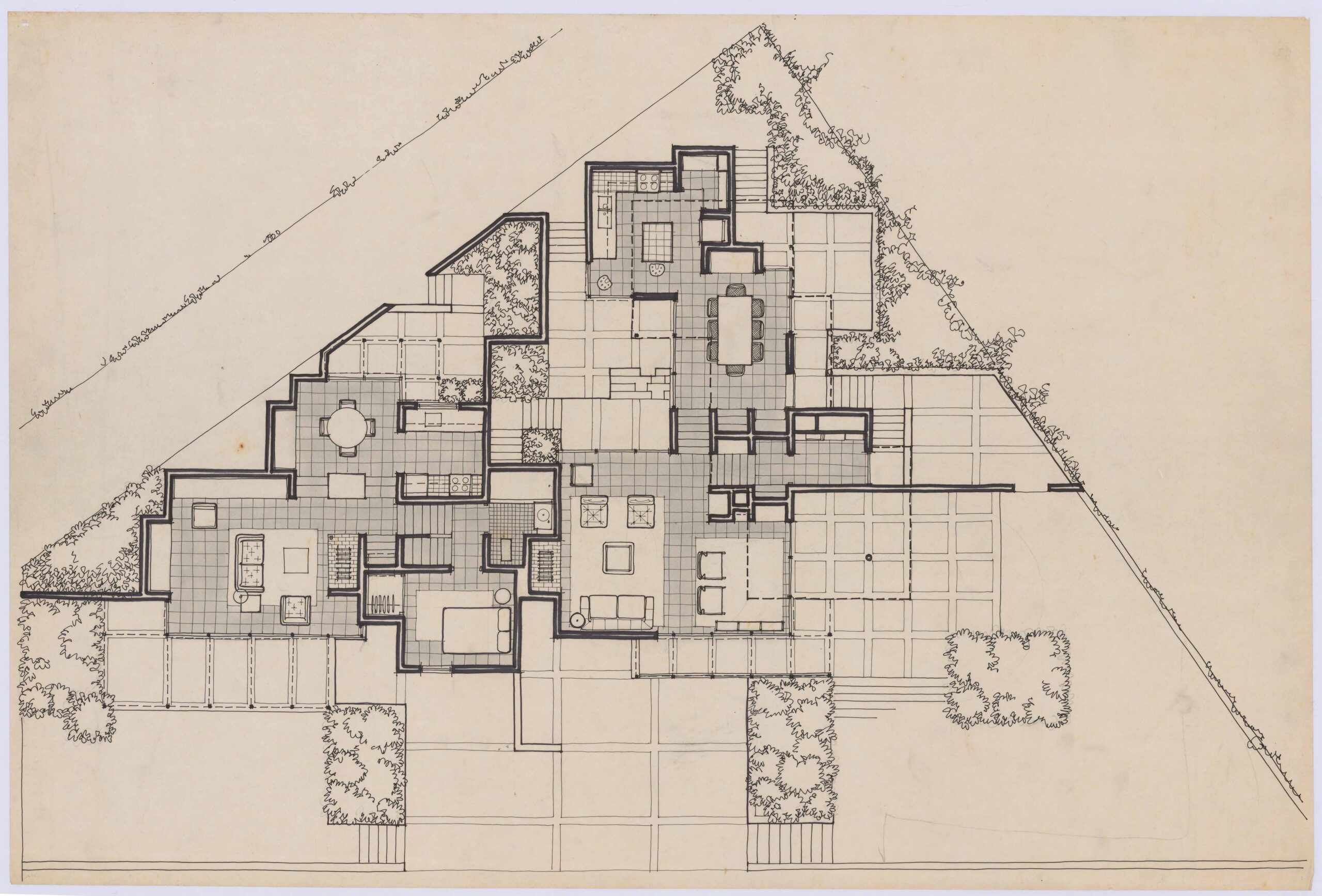

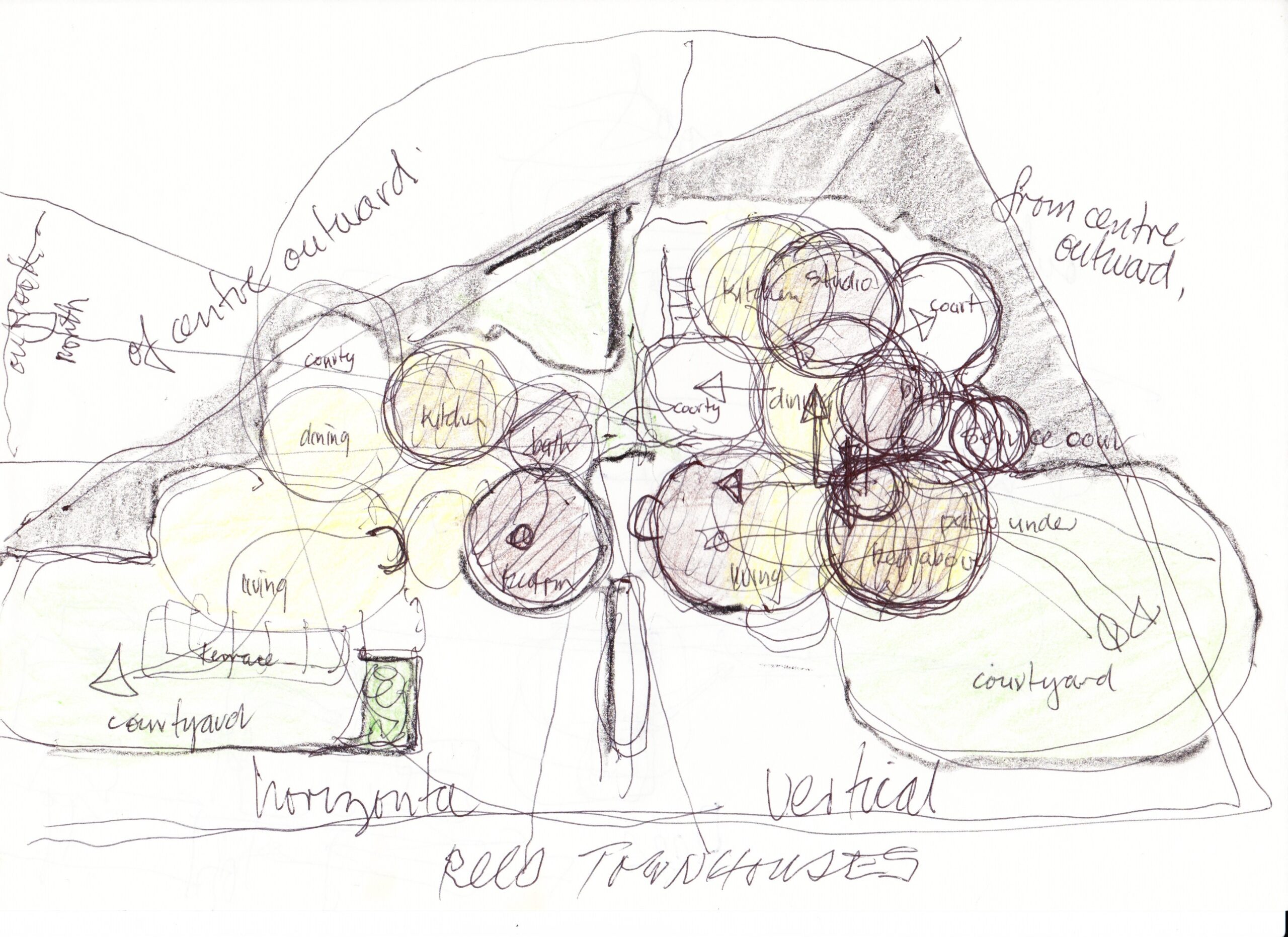

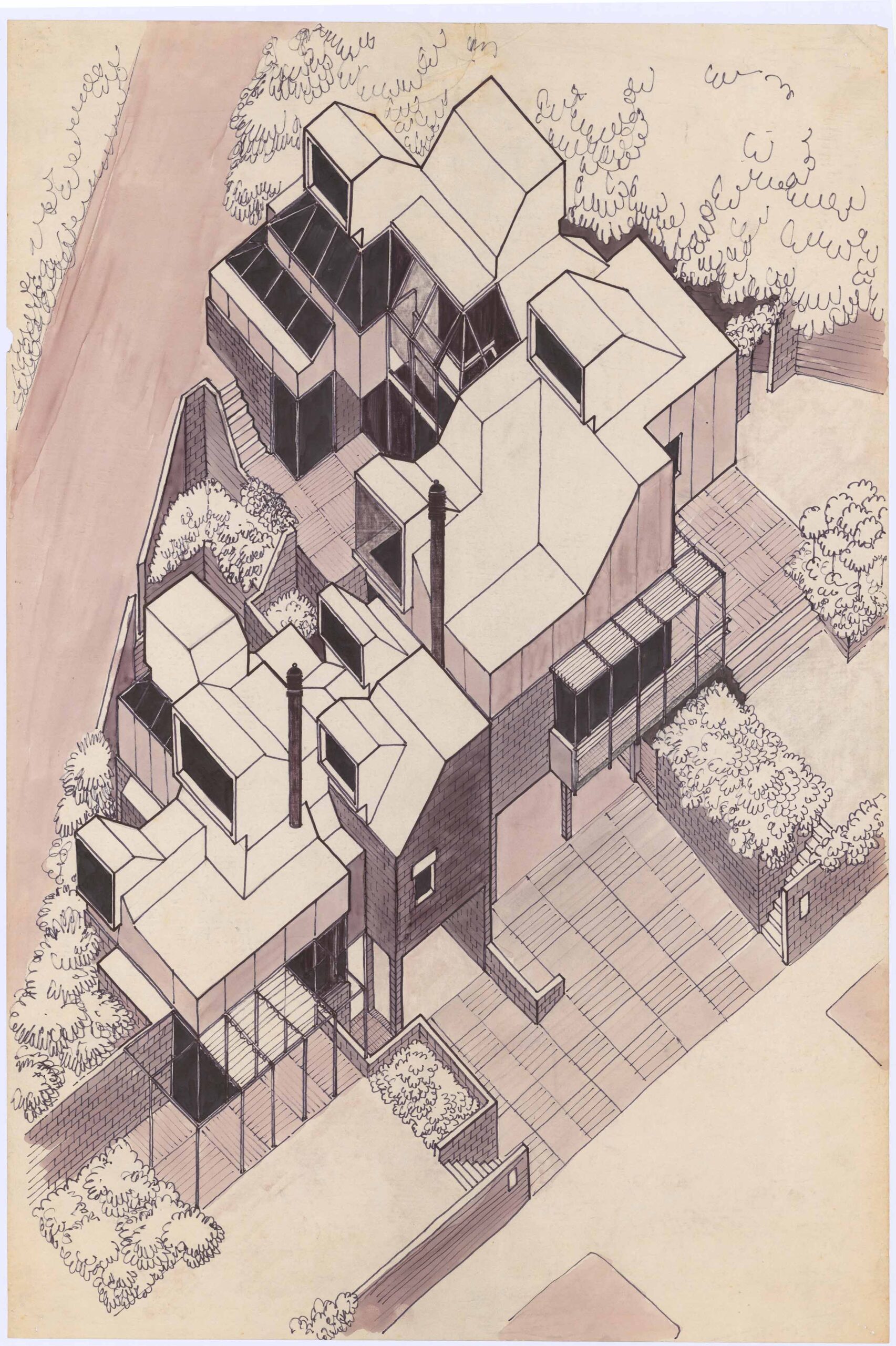

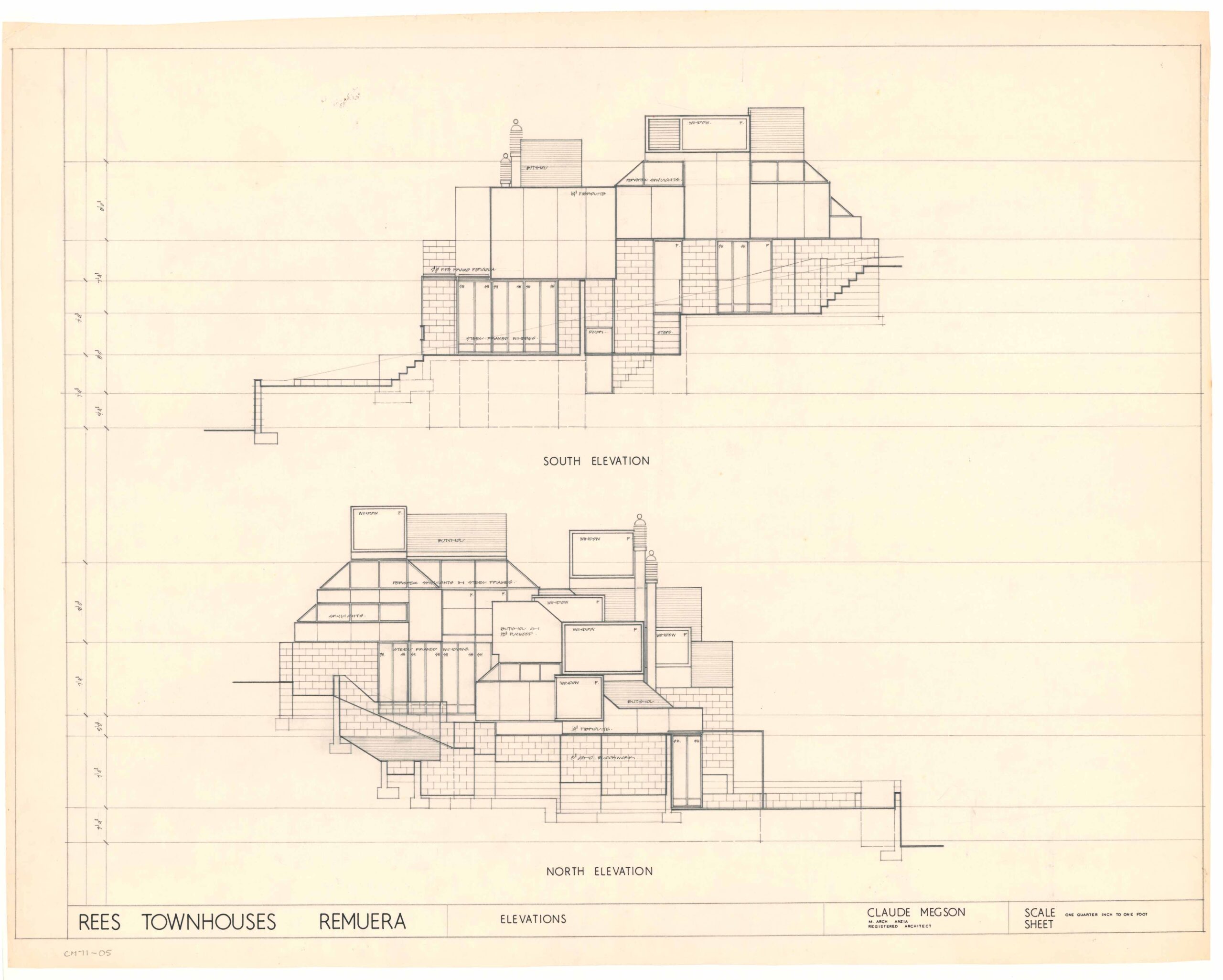

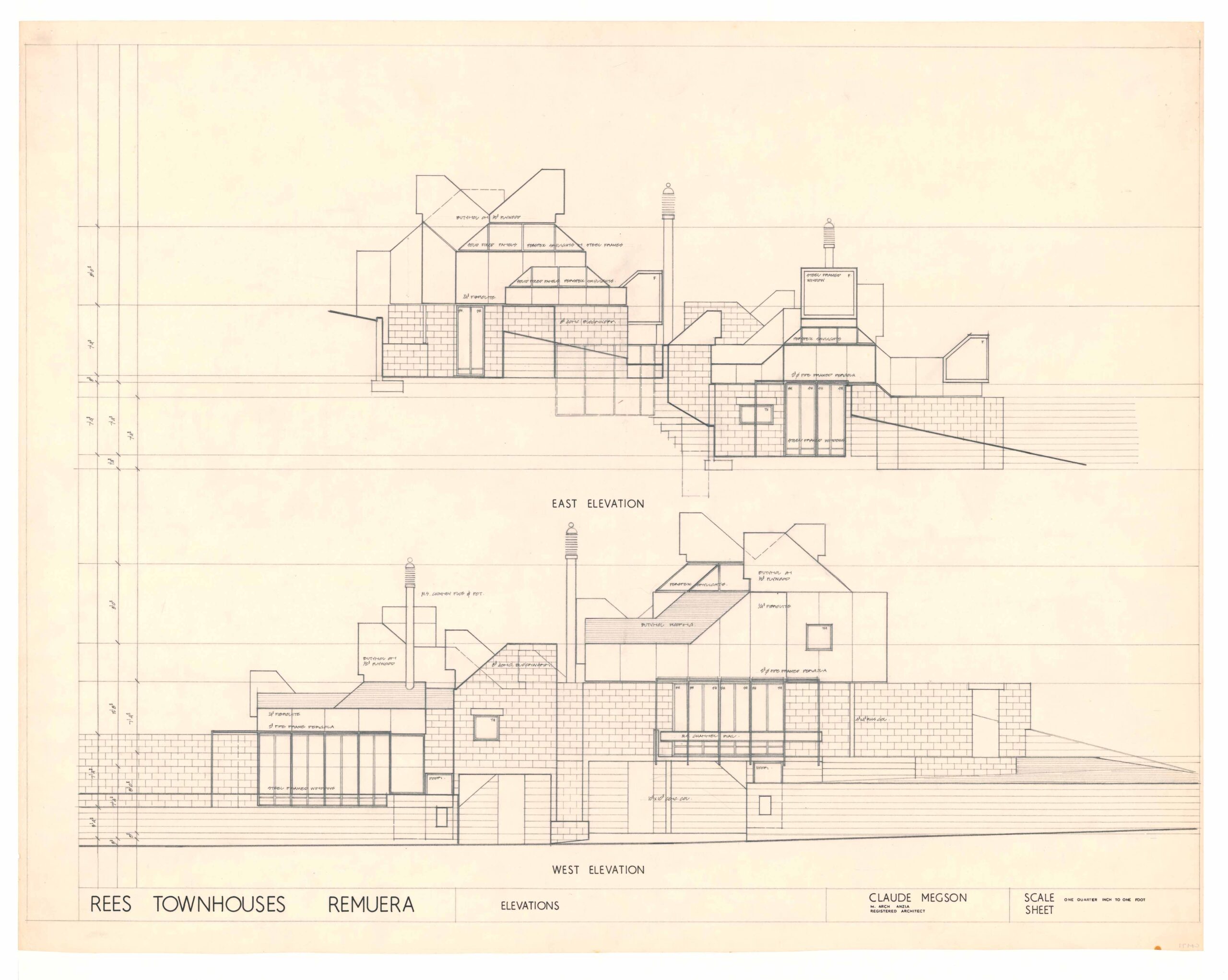

Rees Townhouses Claude Megson Collection. (CM71) Architecture Archive. University of Auckland Libraries and Learning Services

Rees Townhouses Claude Megson Collection. (CM71) Architecture Archive. University of Auckland Libraries and Learning Services

Rees Townhouses Claude Megson Collection. (CM71) Architecture Archive. University of Auckland Libraries and Learning Services

Rees Townhouses, 54 Hapua Street, 1974

The Rees Townhouses are one of Megson’s finest buildings. They were designed for Gavin Rees, who before commissioning them, lived further up the road at No. 1/64 Hapua Street. It is a project in which every aspect of the geometry is controlled and purposeful, where the timing of one’s journey, the orchestration of spatial compression and release, creates an interior of alternating drama and repose.

Being in the house for any extended duration, is to be transported magically to a different place, where the life of the street fades and one enters a Tardis like interior of lofty dimensions. The rise and fall of the platforms are echoed in the roof forms overhead. The planting, which has grown to almost tropical proportions around the house today, reinforces this impression that suburbia beyond simply vanishes when one occupies this building.

The site is triangular in shape, slopes steeply uphill from the street and is obviously extremely awkward to design anything upon. These sizeable constraints might have led to the view that the site could only accommodate one house. Megson managed to get two units on it. He deployed a then in-force planning rule conceived to address corner plots. This only required the architect to set back the house on the street frontage. Here this allowed him to argue he could build hard to the other two boundaries.

The townhouses read as one, or alternatively, as father-son or mother-daughter pairings, which riff on the same themes. The lower townhouse was designed with a single bedroom, and the upper with two. Both units sit over two garages, dug into the slope. The front doors are tucked away. One enters next to the car and tunnels upwards, via a series of tight turns, climbing stairs which bring one into the centre of each plan. The rooms themselves are, once again, small. Megson puts each room on a distinct level. Every room connects to another without any hall or corridor. Every space has access to at least one external courtyard, the larger rooms have two.

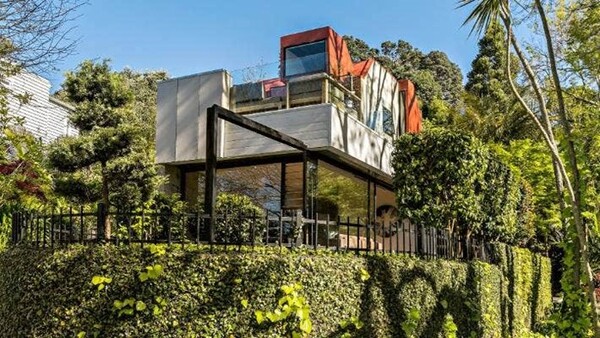

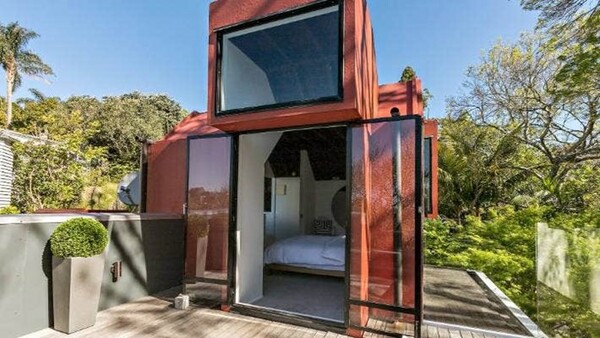

The roof consists of periscope forms which rise, crank at 45 degrees and look out horizontally. Most periscopes face north, a few look east. As well as adding to the amount of illumination, the zenithal light, adds to the sense of being cocooned within the site, as also occurs further along the road at No.64 Hapua Street.

Walls which retain the earth are unpainted reinforced concrete masonry. Walls which float above the blockwork are constructed from timber stud, sheathed in white painted hardboard. Their expressed joints suggest the discipline of a planning grid. Shadow gaps delineate their edges, created by painting the studwork behind black. Dark stained timbers cap balustrades and upstands. External windows and doors are extruded slender steel sections, probably Pillar AHI Flush Steel Windows, based on the 1930’s English Crittal Windows system. Ceilings are dark stained rough sawn timber planks. Roofs were originally flaming red Butynol. Contemporary photos show what a rude shock this new building would have been to the neighbourhood.

Architects Bull O’Sullivan altered the lower unit in or around the mid to late 2000’s. The practice showed little engagement with Megson’s design or philosophy, and the project is no longer on their website. The architects removed Megson’s quick repeating steel windows, replacing them with a giant glass sliding window, suspended from a Richard Neutra-like steel frame which projects into the garden. A new top floor bedroom opens onto a roof deck, surrounded by plate glass barriers. Here, silver aluminium cladding replaces the original fibre cement sheeting. These significant alterations went unremarked upon when the townhouse went on the market in 2018, and the work was advertised for its impeccable Claude Megson credentials.[29] While it would be nice to reason that the complete clash in architectural styles should be obvious to most, it is disconcerting to know these changes are now confused with Megson’s original concept.

The upper townhouse, by contrast, has been restored patiently and sensitively over many years. The client’s brother, architect Dominic Glamuzina, at the time in partnership with Aaron Paterson, added a clever and stylistically in-tune bathroom wing in the early-to mid-2010s.[30] Although a small-scale intervention, it offered one of the early signs that for a younger generation, there is renewed desire to engage with the major architectural legacy of Claude Megson.

Special thanks to Sarah Cox, Archivist (Special Collections), Cultural Collections, Te Tumu Herenga | Libraries and Learning Services, Waipapa Taumata Rau | University of Auckland.