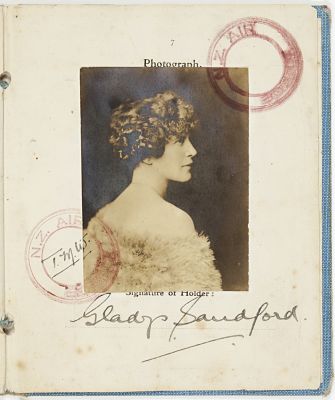

WW1 Gladys Sandford ( Henning, nee Coates) MBE (87100)

Portrait of Gladys Sandford. Gladys Sandford papers, ca. 1891-1925. (State Library of New South Wales collection of World War I papers).

Gladys Sandford was the first woman in New Zealand to work as a car sales representative and also to attain her pilot’s licence.

Gladys Coates was born in Sydney on 4 March 1891, Australia and her family moved to New Zealand when she was a child. At the age of 21 Gladys was employed as a schoolteacher at Napier. On 20 June 1912 at St Barnabas’s Anglican Church, Mount Eden, she married William Henning, a widower and a motor car importer and salesman. She learned to drive and enjoyed tinkering with engines. [1]

When her husband enlisted in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force in 1914, Gladys offered her services as a motor driver, but was turned down. She joined the Volunteer Sisterhood under Ettie Rout – it cost £130 to equip, insure and finance a volunteer to Egypt for one year; £70 was raised while Gladys was living in George (Ohinerau) Street, Remuera. She chose to pay the remainder herself and sailed on 30th December 1915 to be a hospital orderly and nurses’ helper. [2] [3]

Her husband, William Henning, was already stationed there as a solider in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force. She faced treacherous roads and rocky conditions as an ambulance driver, but this didn’t stop her helping those who needed her. When her husband’s battalion moved to France to fight against the German Army, Sandford joined him in England, taking up a job as a cleaner in the Hospital. In May 1917 she persuaded the Sergeant Major in charge of the drivers to allow her to work as an ambulance driver with the Motor Transport Section of the N.Z.E.F. at Hornchurch and Walton-on-Thames hospitals. She rose to be head female driver. [4] [5]

Her husband Lieutenant William Henning, earlier awarded the Military Cross “for conspicuous gallantry and resource” died of wounds on 13 September 1918. Gladys’s brothers did not survive the war either: Randolph Coates of Remuera died of wounds in Belgium in June 1917 and Eric Coates died of pneumonia in Auckland in November 1918, just days before the war ended. Devastated by her losses and exhausted from her war work driving motor cars, Gladys contracted the deadly influenza virus of 1918. While she did recover, the ‘flu permanently damaged her lungs. [6]

For her hard work, Sandford was awarded an M.B.E, Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire in 1920. [7] Unfortunately because she had not attested in New Zealand and was employed in a civilian/voluntary role with the NZEF in England, Gladys found that when she applied for war medals in New Zealand that she did not qualify for them. However, a ruling by General Richardson said she was to be treated as a special case and have all the privileges of a returned soldier granted.

She was the first woman to receive full membership of the Auckland Returned Soldiers’ Association and wear the RSA badge, thanks to her two years’ service abroad with the New Zealand motor transport with the rank of driver.[8] Her address in Remuera was given as her parents’ house, Waimana, Hastings Rd, (now Haast St) Remuera. (18/4/1920). [9]

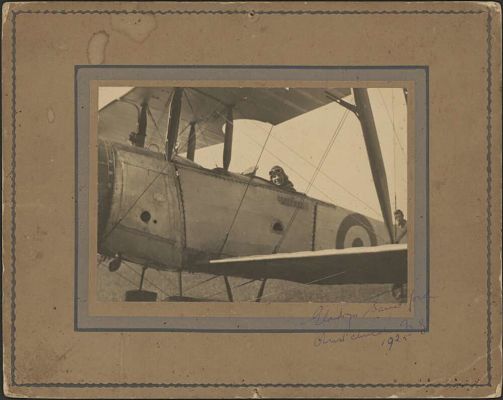

Gladys remarried in 1920 to one of William’s close friends, Squadron Leader Frederick Esk Sandford (d.1929), an Australian serving with the Royal Air Force. The couple lived in England, India and Egypt. But the marriage did not work out and Gladys’s lung condition worsened, so she returned to New Zealand alone in 1923. Spending almost a year in bed, Gladys was ordered to live a quiet life.

In December 1925, despite strong opposition, she became the first woman in New Zealand to gain a pilot’s licence (No.18). Gladys said “I am not doing it for a joke’ she said “I am learning to fly because it is going to be a commercial proposition. I admit there may not be much in the business just at present but when there is I will be ready for it. If I find I cannot make it pay in the Dominion then I will go to America.” The new flying recruit was said to be a motorist of unusual ability. When she left Auckland it was in a motor-car and she drove it to Wellington in 20 hours 30 minutes. [10] Sadly, though, she never flew again after this, because flying was too expensive. Gladys had to refuse an offer by an Australian syndicate to finance her on a solo flight across the Tasman Sea. “I was sorry to refuse the offer,”‘ said Mrs. Sandford, “but I was not in good health and the doctors would not give me permission to undertake the journey.” [11]

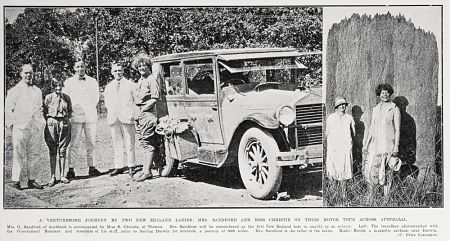

Forced to support herself, Gladys worked as a motorcar saleswoman and taught her customers to drive. She was dared to emulate F. E. Birtles’ overland trip from Adelaide to Darwin. Gladys then embarked on another adventure, to drive across Australia east to west and north to south. On 4 March 1927, she set off with her friend Stella Christie, who could not drive, to attempt this feat, in a 1926 Essex 6 coach. Their equipment consisted of tinned foods and flour, a frying-pan, a billy and a grid-iron, blankets and a mattress, canvas waterbags, a tomahawk, fencing wire and a wire strainer, a set of bog extractors, a Red Cross outfit, a revolver, and four suitcases of personal luggage. The only spares they carried when they set out were two spark plugs, a coil, and a soldering iron. They encountered floods, impassable roads, crocodiles and snakes. The car repeatedly broke down, but Gladys made all the repairs. One time, in the middle of nowhere with a broken clutch, Gladys short-circuited the Transcontinental telegraph line. A repairman sent to locate the problem was very surprised to find the stranded women, but arranged for a new clutch to be sent.

Gladys and Stella returned to Sydney on 25 July 1917, having driven a distance of 17,600kms, and became the first women to make the crossings. [12] [13] The travellers crossed Australia four times and covered 11,000 miles. They started on March 4 and drove from Sydney to Perth and back to Adelaide. Thence they went to Darwin and back and returned to Sydney. The motorists had an adventurous time in the wild and little-known country of the Northern Territory, but they overcame all difficulties without mishap. The tour began at Sydney. Passing through Melbourne they reached Adelaide and set out for Perth, encountering very difficult conditions on account of heavy rain. They had intended making for Darwin, via the west coast, but many streams were in high flood. They therefore returned to Adelaide and started for Port Darwin by way of the cable track through the heart of the continent. They reached their destination without mishap, but on the return trip they ran out of supplies at Barrow’s Creek and had to remain there for four weeks. The travellers had to ride 65 miles on horseback to the nearest telegraph office. After this delay they continued without mishap to Adelaide and thence via Melbourne to Sydney, where they received a warm welcome. [14]

Afterwards Gladys wrote about her adventures in Australia in newspaper articles called Sand and Spinifex (Auckland Star, 12 November 1927) and toured New Zealand extensively giving talks to the public.

In 1929 Gladys settled in Sydney. During World War II she founded and presided over the Women’s Transport Corps. By 1940 it had almost 400 members who had to practise military drill, and pass theoretical and practical examinations in driving and maintenance. The unit was soon brought under the umbrella of the National Emergency Services. By day she censored letters for the Department of the Army. After the war she ran a poultry farm with a female friend for a few years before obtaining a job with the Department of Repatriation. In 1956 she retired. Gladys moved into the War Veterans’ Home, Narrabeen, worked at the home’s art-union office, took up painting, and enjoyed sea fishing. A vice-president of the Sydney branch of the New Zealand Returned Soldiers’ (later Services) Association, she marched on Anzac Day and acted as an unpaid social worker for the association, visiting sick and distressed soldiers and their families. Gladys died on 24 October 1971 at the Repatriation General Hospital, Concord, and was cremated. [15]